PREFACE

This short history is arranged in four parts. First, a brief introduction; second, the story of the firm of Urquhart-Dykes & Lord up to 1939; third, the story from 1945-1991; fourth, character sketches written by Peter Lord of Bill Urquhart-Dykes and himself.

Readers will notice that there is some difference between the treatment of thedddsecond and third parts. My sources for the earlier part were the writings of Hardingham and Fairburn-Hart (and indeed others on the early history of the profession of patent agent) and, to a large degree, the written and oral memories of Peter Lord. Since this period ends before the birth of the majority of readers, I have thought it right to go into rather more detail in certain respects than was necessary or desirable in dealing with more recent periods.

I am grateful indeed to those past and present members of the firm who have helped me research and write this short history; particularly to Peter Lord for unstinting help, kindness and hospitality (although I cannot but think that this history should have been written by him, not me); Michael Wisher for immense help and encouragement throughout; Steve Walters, the present senior partner, particularly for trusting me with much confidential material; David Geldard, the senior partner from 1989 to 1991; and Ronnie Harris for setting me right on dates and locations. Also to Ivor Davis CB, lately Comptroller-General of Patents, Designs and Trade Marks. But, of course, any omissions and any errors of fact, interpretation or emphasis are my own.

John Longrigg

THE SCRIBE

J S Longrigg CMG OBE spent 34 years in the Diplomatic Service. After his retirement in 1982 he developed an interest in Intellectual Property through acting for three years as Administrator of the Common Law Institute for Intellectual Property.

PART I - INTRODUCTION

The profession of patent agent or patent attorney (as it is known in most countries) involves practice in several fields of intellectual property law, namely patents, registered designs, trade marks and copyright. In the early days of the 19th century, patent agents were generally persons who purported to assist inventors through the jungle of regulations leading to the grant of Letters Patent for an invention. Their involvement in the other aspects of the profession, indeed their evolution into a recognised profession was gradual.

The firm of Urquhart-Dykes & Lord may, in one sense, be said to date from 1946, because it was in that year that it acquired its present name. But the real origins of the firm go back some seventy years earlier to the 1870s, and it is there that our story must start. In that decade two young men set up, quite separately, one in London, one in Leeds, as patent agents. Both continued to practice into extreme old age. Both practices were acquired in the 1920s and 30s by William (Bill) Urquhart-Dykes, who merged them into a single practice in which he was joined as a pupil in 1934 by F E (Peter) Lord (who was taken into partnership in 1946), and which continued to maintain offices in Leeds and in London. The post-war years saw an expansion of the firm so that by 1991 it operated out of fourteen offices in the UK, and had eleven partners. This expansion was partly the result of the incorporation of a number of smaller practices and (in 1987) of a major merger with the practice of Michael Burnside & Partners.

A great deal has changed since the 1870s. But what has not changed is the essential nature of the main characters in this study, from the earliest days to the present, and this is conveniently defined by the words of the title of this history, which were written in 1862 by a Mr Hindmarsh QC who was a member of the Royal Commission appointed in that year to enquire into the working of the patent laws. The Act of 1852 had greatly simplified the procedure of obtaining a patent (though it still remained very complicated) and reduced the fees from about ,300 to ,25. This led to a sharp increase in the number of applications for patents: consequently the number of patent agents (who do not seem to have numbered more than a dozen or so before 1852) began to increase. Many of them were unqualified and some were unscrupulous rogues. Mr Hindmarsh noted this: Grossly incompetent and fraudulent persons have acted as patent agents, to the great loss and injury of many inventors induced to employ them. But he acknowledged that some patent agents are persons of skill and probity. Mr Hindmarsh's recommendation was, of course, that the profession should regulate its members so that only qualified, competent and honest practitioners should be registered and allowed to describe themselves as patent agents. But another twenty years went by before the inauguration of the Institute of Patent Agents in 1882, followed by the compilation in 1889 of the Register of Patent Agents and the Institute's incorporation by Royal Charter in 1891.

The careers of both of our founding fathers demonstrate that, unlike some of their contemporary competitors, they were indeed persons of skill and probity. We will return to the detail of those careers later. But in them it is possible to discern certain elements which seem, like a genetic strain, to have survived to the present day. Skill and probity we can take for granted nowadays but, in addition, we can note a series of strong characters, with a sense of dedication and a ruthless eye for detail and with, in some cases, a striking talent for some activity outside professional life. The strength and prosperity of the firm has come from the individual quality of its members and continues to do so.

PART II - UP TO 1939

The London Office : from early days to 1927

Until he was joined in partnership in 1927 by W Urquhart-Dykes, this seems to have been a one-man practice in the person of George Gatton Malhuish Hardingham. Born in 1848, educated in Germany and at King's College School, London, he was trained and qualified as an engineer, but seems early in life to have begun to practice as a patent agent. From its inception in 1882 he was a pillar of the Institute of Patent Agents: a founder member, he served as its Honorary Secretary from 1882 until its incorporation by Royal Charter in 1891, when he was a member of the first Council; its Hon Secretary until 1902; its Vice-President and then President 1903-05; and finally Honorary member in 1930 till his death, at the great age of 91, in 1939. He had retired from the firm in 1929. The firm's offices in 1927 were in Surrey Street, WC1 but were moved, after Hardingham's retirement, to Chancery Lane.

Hardingham must, in his prime, have been a formidable man as well as a distinguished member of the profession; and it is possible to form some impression of his character from his writings. He published in 1891 a booklet Patents for Inventions and how to procure them, and, after the coming into force of the Patents and Designs Act of 1907, a booklet entitled Patent Rights, their Acquisition and Maintenance. A second edition of the latter work was published in 1912. It is written with impressive force and clarity, and the general tone is of considerable self-assurance: you get the impression of a man whom it would be difficult to contradict, and who would not relish contradiction. The same impression is given by the loose leaf Procedure Book which he left with the firm on his retirement; here too is evidence of a scrupulous regard for detail. The personality who can be dimly perceived through these works is one who might inspire respect rather than affection. This perception is confirmed by the impression which he made on Urquhart Dykes when the latter joined him as a junior partner in 1927. Hardingham was already 79 years of age, and struck Urquhart-Dykes as fussy, meticulous and quarrelsome both with his clients and his staff. He was, understandably, well past his best by 1927 and the firm had been losing business; but it had retained enough of its long-standing clients for Urquhart-Dykes to restore its fortunes.

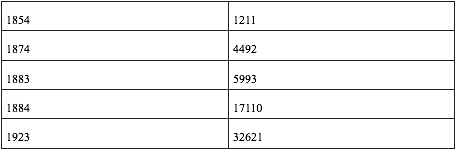

Hardingham's long and successful career coincided with profound changes in the nature and status of the profession of patent agent. The position before 1883 has already been mentioned, but the establishment in 1889 of the Register of Patent Agents did not at once give to the profession the respectability and status which it rightly sought, since any person practising as a patent agent before 1889, however unqualified or incompetent, could have his name placed on the Register. Thus for the first part of his career Hardingham, as a leading spirit in the foundation of the Institute and its Hon. Secretary, was in the van of those who sought successfully to clean up and regularise the profession. At the same time, the number of applications for patents - and thus the volume of work for patent agents - was rising as the result of successive legislation: the Act of 1852; the Trade Marks Act of 1875; the Patents, Designs and Trade Mark Act of 1883; and the Act of 1907. All these had the cumulative effect of reducing costs and simplifying procedures; and these factors, combined with the effects of an era of rapid technological advance, increased the number of patent applications:

No wonder that, in the last quarter of the 19th and the first quarter of the 20th Centuries there was plenty of work for Hardingham and his contemporaries. The emphasis of the work of the patent agent was also changing, in that the importance of the purely procedural side decreased as the procedures in the UK were progressively simplified, while the emphasis on technical and scientific understanding, and skill in drafting, was of increasing importance as was expertise in the Intellectual Property Laws of the component parts of the British Empire and foreign countries.

The Leeds office: up to 1934

Almost contemporary with Hardingham was William Fairburn-Hart, who was born in 1853 and who by 1933 had practised as a patent agent in Leeds for 59 years. Like Hardingham, Fairbum-Hart was also an author on professional topics. One booklet that survives was published in 1889 and entitled Trade Marks: Their Object, Use and Protection in Great Britain and Ireland. In 1924 he celebrated 50 years of practice by reading a paper to the Chartered Institute entitled Fifty Years of Patent Agency. The mere fact of having been invited by the then President to deliver such a paper must indicate that Fairburn-Hart was a person of some substance in the profession. The paper itself still reads well; and is indeed of interest to an historian of Intellectual Property in this country. Fairbum-Hart looks at the procedural complexities before the 1852 Act; and at the position after it. The Act had created a Commission consisting of the Lord Chancellor, the Master of the Rolls, HM Attorney-General and Solicitor-General for England, the Lord Advocate, HM Attorney-General and Solicitor-General for Ireland. All applications for patents were referred to the Attorney-General and Solicitor-General for England (who dealt with them alternately, one taking the even numbers and the other the odd numbers). The applications had to be left at the Patent Office by hand - which of course meant that provincial patent agents such as Fairbum-Hart had to maintain a London correspondent or filing agent.

Fairburn-Hart's paper describes the consequences of this system and provides some lively detail: for example it was once necessary to pursue the Lord Chancellor to Balmoral to receive a petition for the issue of a duplicate of Letters Patent.

Fairburn-Hart's professional reputation was high and his relations with his clients good. But he was certainly a man of strong character and explosive temper: a senior member of the Patent Office in the 1930s remembered the unannounced arrival from Leeds of Fairbum-Hart insisting on interviews and exploding with rage if they did not proceed as he wished. By 1933, at the age of 80, his practice had declined and he was in no condition to keep it going. However he still commanded the loyalty of his secretary (Miss Alice Turner) and his technical assistant (Mr John Selby). Fairbum-Hart himself, long past active work, would spend his days in the office until shortly before his death in 1936. He seems to have had little life outside the office and rests in an unmarked plot in Lawnswood Cemetery in Leeds. It has been said that in those days he resembled a small Father Christmas. We may leave him there, in the middle thirties, seated at a desk in a comer of Miss Turner's office, copying out, in meticulous longhand, passages from the Reports of Patent Cases.

Urquhart-Dykes and Lord

As indicated above, Bill Urquhart-Dykes joined Hardingham in 1927 as junior partner. In 1928 the firm moved to 75 Chancery Lane. Hardingham retired in1929. By 1933 Bill Urquhart-Dykes had restored the practice to much of its former prosperity and was looking for expansion. Learning that FairbumHart's practice in Leeds was for sale, he bought it for ,.500 in 1934, combined it with the original Hardingham practice; and ran it by means of fortnightly visits. In 1934, Peter Lord joined the firm as a pupil and qualified in 1937. The Chancery Lane offices were bombed in the early months of World War II and the firm's offices were moved to Ealing with those of Mewbum Ellis & Co, the firm of patent agents in which Urquhart-Dykes had been apprenticed. However both Urquhart-Dykes and Lord had volunteered for the RAF and were called up in the spring of 1940. During the war years little patent work was being done and the firm was 'care-taken' by Mewbum Ellis & Co. Urquhart-Dykes was invalided out of the RAF as a Flight Lieutenant early in 1945 and began to pick up the pieces of the practice. Lord returned to the UK as a Wing-Commander and to the practice at the end of 1945. The firm moved back to London in early 1946 - by chance to Arundel Street off the Strand: very close to the site of Hardingham's original practice.

Peter Lord was taken into partnership and the two firms renamed accordingly - Hardingham and Urquhart-Dykes plus W Fairburn-Hart & Co were merged as Urquhart-Dykes & Lord (UDL), the style which they have retained.

This is the bare outline of the firm's story between 1927 - 1946. It is time to look a little more closely at the dramatis personae.

If this story has a central character, linking the early history of the Hardingham and Fairbum-Hart practices with the modern firm which bears his name, it must be Bill Urquhart-Dykes. Born in 1897 in India where his father was serving as a regular officer in the Cameronians, Urquhart-Dykes was educated at Glenalmond, where he took full avantage of the opportunities for acquiring engineering skills. He left school in 1915 and, while awaiting his call up to his father's regiment, worked for some months in the Motherwell steel works. He had already acquired a motor bicycle. By the end of 1916 he had been accepted by the Royal Flying Corps as a trainee pilot and by July 1917 was flying operationally in France, which he did continuously till March 1918. In May 1918 he was posted to Ireland, where he was, in June 1919, the first to see the Vickers Vimy aircraft, its nose in an Irish bog, which had been flown across the Atlantic by Alcock and Brown the first direct west/east transatlantic flight. He also married an Irish lady, Miss Ruth Hegarty.

On demobilisation, he was apprenticed in 1920 to the well known firm of Mewburn, Ellis as the pupil of George Beloe Ellis, solicitor and patent agent, with whom he had a family connection. He qualified in 1925. As noted above, he joined Hardingham in 1927 as junior partner. For most of the 1920s his principal interest outside the office was motor sport, and in that decade he took part in a large number of trials and races in England, Ireland and the continent and scored a number of notable successes at Brooklands, Le Mans and elsewhere. But in 1929 the demands of the firm on his time made it necessary for him to give up racing, though he retained his active interest in the sport. He also retained a proper pride in his Scottish ancestry and is vividly remembered in the office kilted and playing the bagpipes.

Thus in 1929, Bill Urquhart-Dykes was the sole partner in what had been the firm of Hardingham and Urquhart-Dykes. The remaining staff consisted of two typists and an office boy, Jack Newton who later developed into an excellent trade mark agent. The staff was increased in 1934 by the arrival of, as a pupil, Peter Lord. Born in 1912 and educated at Westminster School and Trinity College Cambridge, Lord had read classics and architecture - the latter with a view to entering his family firm. But a disinclination towards this career, and personal friendship with Mr & Mrs Urquhart-Dykes, led him to accept a suggestion from Urquhart-Dykes to join him in the practice. He qualified in 1937. His memories of the period show Urquhart-Dykes as the true heir to the virtues of probity, skill and meticulous attention to detail which we have seen in the person of G G M Hardingham without however, the latter's less endearing characteristics. Lord himself was heir to these traditions, and also to the notion of a strong interest outside the office. He became a keen sailor of small boats and was for some twenty years a committee member and eventually commodore of the 'Wayfarer' dinghy class. It may not be too fanciful to suggest that such 'outside' distinctions and interests may have given an additional dimension to the individuals who came to make up the firm. We shall see this pattern repeated.

It is also worth noticing that the close professional association of Bill Urquhart-Dykes and Peter Lord was mirrored by close personal friendship. Lord, in fact, shared flats and houses with Urquhart-Dykes and his wife Ruth until their deaths, and the three of them would take their holidays together every year, usually fishing in the west of Ireland close to where Ruth had been born.

By 1939, Peter Lord was handling most of the patent work of the firm, while Bill Urquhart-Dykes concentrated on trade marks. The firm was prospering. It had inherited from the Hardingham and the Fairburn-Hart practices some substantial clients, although it had been hard work getting the two practices back to their original state.

We are now about to reach the post-war era. By 1946 the firm, after the wartime lull, was again active under its two partners. A new recruit, Michael Wisher, was brought into the Leeds office. A new phase of growth and expansion had begun.

PART III - 1946 TO 1991

The story of the next forty-five years of the firm of Urquhart-Dykes & Lord is, in essence, its evolution from a small family firm to one of the half dozen largest firms of patent agents in the United Kingdom. This evolution was slow to take off and did not reach its full impetus until the 1970s and early 1980s. It came partly as a deliberate and planned response to changing economics and professional conditions; partly by seizing opportunities as they arose; but mainly from the personalities of the partners themselves and their changing perceptions of the sort of firm they wanted - and, in this context, questions of site and of location were crucial.

Fortunately for its chronicler, the state of the firm on the 27th of September 1946 is vividly illustrated in the minutes of the first meeting of all the London staff held on that day. Present were the two partners, S J (Jack) Newton (trade marks), and the five ladies who looked after the registry, the accounts and the secretarial work. The two members of the Leeds office staff, John Selby and Alice Turner, were not present but it was agreed that they should attend subsequent meetings. The main topics were the change of the firm's style and its forthcoming move to Maxwell House in Arundel Street (between the Strand and the Embankment). The ramifications of the move were debated in great detail - down to the lino on the floor, and the installation of the telephone. Nearly half a century later, the reader has the impression of a very small organisation picking itself up and dusting itself down after six wartime years of hibernation.

This impression is not altogether false. The kind of economic and industrial activity which provides work for patent agents had obviously been at a low level during the war years, and took some time to recover in the years immediately following 1945. Both the London and the Leeds offices had kept most of their pre-war clients; and indeed the Leeds office had somehow managed throughout the War to continue to act for certain clients on the European mainland. But there was not much new work; this would have to await the dramatic upsurge in economic and industrial activity throughout western Europe as the result of the Marshall Plan.

Bill Urquhart-Dykes and Peter Lord remained the only two partners in the firm from 1946 to 1962. Both men were dedicated to their profession, and were successful, well-known and highly respected senior members of it Urquhart-Dykes particularly so in the field of Trade Marks (he was President of the Institute of Trade Mark Agents from 1952-55 and was created the first President Emeritus of the Institute in 1977, shortly before his death in January 1979). So it is no disrespect to either of them to say that what they aimed at professionally was essentially a small family firm profitable only to the degree which enabled the two partners, after staff salaries and overheads had been paid, to live comfortably and pursue their joint lives and interests as they wished. With Ruth Urquhart-Dykes they constituted a compact family unit and continued to do so until 1979. Peter Lord recalls that in the early days of his partnership it was not unusual to file a patent application for three guineas, one third of which was net profit!

However, it was the Leeds office which Michael Wisher joined in 1946 - directly from school, having discovered in himself a facility for technical drawing, a gift which was nurtured by the long serving John Selby. He turned his period of National Service to good account by adding to his technical and mechanical knowledge through service with the RENTE, and rejoined UDL in 1949. Seeing that his prospects of broadening his experience would be greater in London than in the Leeds of that period, he transferred to the former - the first pupil to be taken on by UDL since Peter Lord in 1934. Michael Wisher found an affinity with trade mark work and qualified as a trade mark agent in 1955 and as a chartered patent agent in 1960; becoming a partner in 1962 and senior partner from 1979-1987. It has been a recurring theme of this history that the senior members of UDL have been persons, not only of skill and probity, but also distinguished in some other field with no connection with the profession of patent agent. This is as true of the third Senior partner as of his two predecessors. Michael Wisher showed a precocious talent for chess, competing at the age of sixteen in the English Junior Championship at the Hastings Congress. But this was overtaken by his prowess at golf. A scratch player for many years he has been amateur champion of Kent and captain of the county team.

We have now reached the early 1950s. Leeds is static, but there is a steady build-up of work in the London office. The trade mark side is handled largely by Bill Urquhart-Dykes, assisted by Jack Newton and Michael Wisher. The patent side is mainly in the hands of Peter Lord and Michael Wisher. Considerations of space in the Arundel Street office made it impossible for UDL to recruit more resident staff, and Peter Lord was able to keep on top of the patent work largely by employing outside consultants, of which the most notable was a certain Frank May. The firm's accounts were from 1947 kept by Reuben Harris, and it is pleasant to record that they are now (in 1991) kept by his son Ronnie, now based (again for reasons of office space) in the firm's Bradford office; and that the third generation, in the shape of Ronnie's daughter, Trudi, also works in her father's department. Records, reminders and renewals were under the care of Bill Greenwood; and it is worth noting that the accuracy of this department of any firm of patent agents is vital to its continued success. Nor is this routine; it involves the timing of a multiplicity of actions in countries with different laws and procedures and an error can be fatal to an application. This may seem a point too obvious to be worth stressing, but it is relevant to the decisions which UDL (in common with large sections of industry and the civil service) had to take in the 1970s and beyond about transferring these functions to computers; these decisions, as we shall see, were vital to the deployment and operation of the firm.

The increase of work in the London office led, in 1962, to the recruitment of Frederick Walters, who became a partner in 1973; and, in 1991, became the senior partner. His arrival in UDL's London office was not auspicious. On his first day he was asked to subscribe to a wedding present for Michael Wisher (whom he had not then met). And he was told by one of the office ladies that his Christian name was impossible; she re-christened him 'Steve' (no doubt in memory of the first martyr), and Steve he has remained. But his arrival was significant in other ways. He was the first member of the firm to hold a university degree in a technical subject (maths and physics at London University); no partner after 1973 dealing with patents would be without one. Steve Walters had previously been an examiner at the Patent Office; and this transition seems so natural that it is perhaps a little surprising that only one other current (in 1991) partner in the firm (Stewart Gibson) comes from the Patent Office stable. Steve maintains the UDL tradition - that of distinction in a field remote from the profession. He is a Judo First Dan.

Another arrival at the London office in the 1960s was David Mere, although in this case it was really a return to the firm in which he had received his professional training in the 1950s. After broadening his experience with other firms and in industry, he rejoined UDL in 1968, becoming a partner in 1974; and since then has specialised in trade mark work.

By the end of the decade, the London office had outgrown its offices in Arundel Street and in 1969 it moved to Columbia House in the Aldwych, where it was to remain until 1974. This need for more office space was in part caused by the arrival at the London office of a new partner, Philip Hustwitt, who had previously been a partner in another firm of patent agents. This was the first time since the 1920s that a partner had been introduced from outside the firm. In the event, however, the arrangement did not work out and, by mutual consent, Hustwitt left the partnership in 1973.

While the London office was expanding its client base, its staff and its premises, the Leeds office had remained static, with no resident partner (or, indeed, qualified patent agent) and staffed by the same personnel that had served there for many years. No further business was being developed. Something needed to be done if the Leeds office was to play a full part in the firm's development.

In 1969 UDL recruited David Geldard, a physics graduate of Birmingham University, and a chartered patent agent with direct experience of private practice in the north east and of work in a US-based multi-national. In the following year, 1970, he moved to Leeds in charge of the UDL office there; and in 1972 became a partner in the firm. In 1988 he became senior partner. Like all his predecessors as senior partner, he is remarkable for prominence in an activity far removed from his professional interests: he is a notable collector of railway tickets and has one of the finest collections of pre-1922 British tickets in the country.

His brief was to revitalise the Leeds office, and build up new business in the industrial heart of England. This he did, mainly in the West Riding of Yorkshire.

We have now reached the 1970s, a decade in which the firm of UDL had to adjust its philosophy to meet a rapidly changing environment although the full effects of the change of emphasis were not evident until the 1980s.

In the first place, the sheer volume of intellectual property work was rising. It has been recorded that, between 1970 and 1988, the number of patent applications in the twenty-four countries of OECD doubled to over one million per year; and at the same time there was a growing understanding on the part of western governments of the economic importance of intellectual property in the context of world trade - so much so that the US and other OECD countries have made tougher global enforcement of patents and copyrights one of their priorities in the Uruguay round of GATT negotiations. This, incidentally, is despite what is sometimes seen as an underlying trend against protecting intellectual property by patents (as taking too long to establish) in favour of copyright (quicker, though less comprehensive).

Secondly, the establishment in Munich of the European Patent Office (EPO) in 1978 altered the role of the UK patent agent vis-a-vis his foreign clients. Up to then, a patent valid in the UK had to be filed with the British Patent Office in London; and this virtually guaranteed a steady source of activity and revenue for British patent agents. But from 1978, a patent valid in the UK could equally well be filed with the EPO in Munich - and indeed this procedure had the advantage that the patent would then be valid in a number of European countries, and the patentee would be saved the time and expense of multiple filing.

Although, as noted above, the EPO did not open for business until 1978, the implications for UDL were evident by the middle of the decade, and two decisions were then taken. On the overseas front, it so happened that by far the greater part of UDL's overseas client base was in the USA, so a special effort needed to be made to retain the firm's existing US clients. This was to a large extent achieved by demonstrating (by means of precise costings) that UDL was in a position to file as economically and effectively in Munich as in London; and had indeed established a presence in Munich with this object.

Secondly, it was agreed to try to increase the firm's client base in the UK by means of establishing new offices in strategic places - the principal criterion being the level of economic activity. This policy was pursued to the point that between 1975 and 1991 UDL had increased the number of their offices from two (London and Leeds) to fourteen. But its implementation, paradoxically, began with what turned out to be a failure. The firm settled on Birmingham as the first new office since 1934, and all the omens looked favourable. A promising young man - Peter Huntsman - was taken on in 1975 and went to Birmingham to set up and run the office. But it never attracted an expected level of local business, and closed in 1982 when Peter Huntsman married a New Zealand girl and decided to emigrate to Australia.

In retrospect, it seemed that one major mistake was made, that it was wrong to try to start 'cold' in a large and sophisticated business/industrial environment where there were already well-established firms of patent agents. Thus, a second criterion was added, and sights were set to expand into areas where reasonable economic activity was linked to a comparative absence of professional competition.

Meanwhile, the number of qualified staff and of partners in the London and Leeds offices was increasing. In Leeds, we have seen that David Geldard became a partner in 1972. In 1973 Michael Harrison, an Oxford graduate in chemistry, joined the Leeds office and became a partner in 1977, serving in the Leeds office until 1986 when he moved to the London office. He left the partnership in 1990 to join a firm of solicitors in Leeds.

At the London end, the office moved again in 1973, this time to St Martin's House in Tottenham Court Road. In 1973 Donald Turner joined the London office and became a' partner in 1975. He stayed with the firm only until 1978, leaving to join a well-known firm of London solicitors. A specialist in Trade Marks, he later followed the footsteps of Bill Urquhart-Dykes by becoming President of the Institute of Trade Mark Agents.

In 1977 and 1978, the 'old guard' of the firm took their leave. Bill Urquhart-Dykes, by then in his late seventies, ceased in 1977 to act as consultant and went into retirement. He died in January 1979. Peter Lord retired as senior partner in 1978, remaining a consultant till 1982. Michael Wisher became senior partner until his own retirement (and reincarnation as consultant) in 1987.

The rapid build-up of activity in the Leeds office and the recruitment to it of Michael Harrison had by 1977 altered the balance of the firm decisively. The Leeds office, as we have seen, had been a rather sleepy outpost up to 1970. By 1977 it was approaching something like parity with the London office in terms of turnover. For the first time, therefore, the firm had to face problems of control and organisation; the way in which these were faced and solved foreshadowed the more considerable problems of ten years later, when the work of not two but many offices had to be co-ordinated and controlled. The solution - or attempted solutions - of these problems were a long way from the days when Bill Urquhart-Dykes and Peter Lord would decide the firm's policy over a pre-dinner drink. 'Indeed, the increasing number of partners (seven by 1978) and the fact that all these partners had minds and opinions of their own, which they were not averse to expressing, made impossible any continuation of a system of benevolent dictatorship. Instead, the tendency of the firm since 1977/8 has been in the direction of the democratic process in which all equity partners (irrespective of seniority in the firm) have an equal voice.

In 1977, the partners reached a formula for continuous consultation on all policy matters, and indeed many quite minor points of detail. The partners in both offices met separately, and informal manuscript minutes were taken (manuscript in order to preserve confidentiality and the freedom to discuss, eg staff matters) and copies sent at once to the other office, who would use them as the basis for their own next meeting. The frequency of these meetings varied and could be as often as weekly. The minutes have been preserved (and been made available to the present writer), and their informal character makes for lively reading. These meetings were supplemented by full meetings of the partnership three or four times a year. There was, at this stage, no attempt to build a formal mechanism to govern the process of decision making, because with only two offices in play - it was not too difficult to reach a consensus. But later, such mechanisms became desirable because of the greater number of partners and geographical locations involved; and it may be convenient before resuming the narrative of geographical expansion to look briefly at the development of the firm's efforts to govern itself.

From 1980 to 1985, as we shall see, UDL opened offices in Peterborough, Keighley, Middlesbrough, Newcastle, Blackburn, Warrington, Swansea, Milton Keynes - but of these only Keighley (which shortly moved to Bradford) was staffed initially by an equity partner - and geography made it possible for him to join in the deliberations of the Leeds office. So it was possible to continue the Leeds/London dialogue as the basic decision-making process, supplemented by full meetings of the partnership. But the second half of the eighties saw equity partners in charge of half a dozen of the firm's offices, and problem of control and co-ordination became acute - particularly with reference to the computerisation of the firm (of which more later) and the need for uniformity as between the various offices in inputting data into the computer. So it came about that in 1985 the partners appointed to the Leeds office (in which the administrative and computer functions of the firm had by that time been centralised) a 'business manager' in the person of Charles Foote, who already had a good knowledge of the firm having been brought in in 1984 to advise on programming the firm's computer. There was by 1985 a clear need for some system by which routine administrative decisions could be arrived at without waiting for a full partners' meeting, but which would preserve the rights of all equity partners to have a voice in major decisions. In pursuit of this object, the partners set up a management committee which included two partners elected by the majority vote of all the partners (and not necessarily including the senior partner of the day). This system continued until 1988 after which the management committee consisted of three elected partners.

A factor binding the separate UDL offices together had been their joint involvement in computerisation. This came in several stages, the first of which was the implementation of a computerised records system, and the second of which was consolidation and computerisation of the firm's accounts. Both these were handled in the Leeds office. The final stage related to the firm of Computer Patent Annuities (CPA). This was founded in Jersey in order to pay renewal fees on patents, designs and trade marks throughout the world. UDL decided to use the services of CPA in 1979 and were involved in the design of its COMUS system for patent and trade mark records.

COMUS is a way of storing information peculiar to patents, designs and trade marks - although it could readily be adapted for use in other fields and provides a mechanism for a patent agent in the UK to store information on his office computer about the cases he is handling and then, on grant of the patent, design or trade mark, readily pass that information to the CPA computer. COMUS was adopted as the firm's principal record system, replacing the less sophisticated system that had already been installed in Leeds.

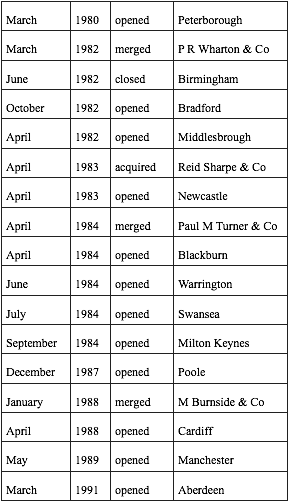

We may now return to the narrative of the firm's development in the period from 1980. This was dramatic, as can be seen from the following table:

The philosophy behind this programme of expansion was that described earlier in connection with the establishment of the Birmingham office in 1975, modified in the light of that experience. The firm would thereafter establish itself where there was a good prospect of a solid client base, building on existing clients where possible. This was partly achieved by acquisitions and mergers with existing smaller firms or individuals whose geographical situation and client base were compatible with UDL's existing structure, and whose staff would fit in with UDL personalities, philosophy and methods of work. Of course there were exceptions and variations and the merger in 1988 with Michael Burnside & Partners was of a quite different order of magnitude.

Thus the locations of the firms present (1991) offices were not indicated solely by their theoretical suitability as determined by their positions on the map; they were also determined by opportunities which presented themselves and were taken as they arose. There was also a further factor. Because two cities or towns look close to each other on a map (particularly a 'flat' map) it does not necessarily mean that business in one can easily be conducted from the other. Bradford looks close to Leeds; but the distance is more than a physical barrier. Swansea looks close to Cardiff, but the people of the former do not take kindly to intruders from the latter. So, while the firm's geographical spread has a logic, it is not a simple or straightforward logic. We may now try to look at the opening of these new offices in a little more detail and do so in roughly chronological order.

Philip Archer, a science graduate of Manchester University and a qualified patent agent with considerable experience in major industrial companies, made contact with the partners of UDL and was invited by them in 1980 to open an office of UDL in Peterborough, where his existing connection with industry could be relied on to provide a viable client base. This proved to be the case. The Peterborough office is conveniently placed between Leeds and London, and has often been the venue for full partners' meetings. It is also well placed to cover the South Midlands, together with the Milton Keynes office (qv). Philip Archer became an equity partner in 1986.

1981 was a busy year. The London office, again under pressure for office space, moved again, this time to Marylebone Lane. The partners agreed to hold two full partnership meetings a year. Talks were initiated with a view to eventual mergers with two small firms, run respectively by Peter Wharton and Paul Turner. Plans began to take shape for the establishment of a UDL presence in the north-east, where David Geldard's earlier stint (with another company) had encouraged him to believe that the ground was fertile. All these beginnings would be realised in the next couple of years. At the London end in 1982 Peter Lord ceased his consultancy.

Peter Wharton had run his own practice since 1975 after graduating in chemistry at Liverpool University and some years experience both in private practice and in industry. He also conformed to the UDL tradition of distinction in a field unrelated to the profession of patent agent: both he and the Beatles (though not together) are reported to have played the guitar at the Cavern in Liverpool. Much of his career was with a major international organisation and when in 1981 he merged his firm with UDL, he was accompanied, as a consultant, by Tony Astell-Burt. Peter Wharton's office was in Keighley, but in 1982 he opened the combined office in Bradford while retaining the firm name of P R Wharton & Co in parallel for a number of years. Given the proximity, he naturally worked closely with the Leeds office and still does so. For reasons of office space, the accounts department of UDL moved from Leeds to Bradford in 1989.

Consideration was given in 1981 to the prospect of opening up in the north-east and this resulted in the establishment in April 1982 of a UDL office in Middlesbrough. In the absence of a suitable and available member of existing UDL staff to run it, the position was advertised and, from a strong field of applicants, Dennis Virr was chosen. A chemistry graduate of Liverpool University, he had enjoyed a long career in both private and industrial practice.

To anticipate slightly, the UDL presence in the north-east was strengthened in 1983 by the acquisition of the Newcastle firm of Reid Sharpe & Co which became available on the death of its proprietor. Thus the Newcastle office of UDL opened in April 1983, looked after by Dennis Virr who also remained responsible for Middlesbrough.

1982 also saw the arrival at the London office of Paul M Turner who, with a science degree and experience both in private practice and in industry, had started his own patent practice in 1977. This was merged with UDL 1983, when Paul Turner became a partner. The new arrival continued the UDL tradition of outside interests and distinction. He was, and is, a yachtsman, parachutist, scuba diver and marathon runner. After a few years in the London office it suited both the firm and Paul Turner that he should move to the West Country (where UDL had not so far been represented) and in 1987 he opened the UDL office in Poole.

In 1984, UDL started to open up in a new area: the north-west; and here the pioneer was Tony Astell-Burt, whom we last met as a consultant concerned with the establishment of the Bradford office. In 1984 he opened offices in Blackburn and Warrington. To complete the north-western story, an office was opened in Manchester in 1989 under George Kelvie, an aeronautical engineer.

Also in 1984, an office was opened in Milton Keynes to strengthen coverage of the south Midlands. This was under the direction of Stewart Gibson, a physics graduate of Durham University, who after three years as an examiner in the British Patent Office, had spent some years in private practice before joining UDL in 1984. As we shall see, he moved to Cardiff in 1988 and became an equity partner in 1990. He was succeeded in Milton Keynes by Roy Marsh, an Oxford metallurgy graduate, with experience both of private practice and of the Ministry of Defence, who had joined UDL as a member of the staff of the Michael Burnside Partnership.

In the same year, 1984, UDL opened an office in Swansea, in circumstances rather different from the opening of the other regional offices in this period. The Local Authority in Swansea had invited applications from existing patent agents to set up shop in Swansea, on the understanding that the Authority would see that intellectual property work in the area was channelled to the new office. It emerged that there was no patent agent already in Swansea, and indeed only one firm in Wales - and that in Cardiff, which for reasons of local patriotism Swansea people did not wish to involve in their affairs. UDL duly applied and were chosen from a shortlist of seven. But since UDL had no suitable person immediately available to open the new offices, they suggested to the Local Authority that they might employ one of the unsuccessful applicants for the post. This was agreed to, and Hedley Austin joined UDL and was appointed to open the Swansea office as a branch of UDL. A chemistry graduate of Nottingham University, he had experience of private practice before joining UDL. He became a partner in 1989.

The Swansea office prospered, and by 1988 had more work than it could handle; so the decision was taken also to open in Cardiff, under the control of Stewart Gibson, previously in charge at Milton Keynes. This expansion into Wales was, of course, not unconnected with the move there of the British Patent Office. Stewart Gibson became a partner in 1990.

We have now covered the establishment of all the present UDL offices. There are a few gaps to fill in the mid-eighties. As we have seen, a business manager had been appointed in 1985 and had served till 1988. Bill Orr, an engineering graduate from Aberdeen University, with long experience in both industrial and private practice, joined the Leeds office in 1986. Bill Orr became a partner in 1990 and was instrumental in the opening of an Aberdeen office in 1991.

By the mid to late eighties, the partners felt that the firm had reached a watershed. As we have seen, there was much discussion on the best way of reaching decisions and of administering what had become a sizeable practice. There were also decisions to be taken about size and scale; an ambitious programme of expansion had been undertaken; where was it to stop? What was the most economic level of staffing? On the one hand, the firm should not become top-heavy with staff; but on the other hand it needed to be in a position to produce scientific expertise in a number of different fields. There was also the question, which arose every few years as leases fell in or numbers became too great to be housed in existing accommodation, of the location of the London office. Given the high level of rents in central London, would it be prudent to move some, or even all, of the London staff to less expensive office in the suburbs? This last question seems to have been resolved, at least for the time being, in favour of remaining in central London. The firm's London office had moved to Wimpole Street in 1988.

In 1988, the size and importance of the firm was substantially increased by the most significant merger since Bill Urquhart-Dykes had merged the Hardingham and the Fairburn-Hart practices in 1934. This was with the London firm of Michael Burnside and Partners, and came about largely because Michael Burnside himself wished to retire, and his remaining partners formed the opinion that they could best continue to provide optimum service to their impressive existing client base (at home and overseas) by merging with a larger firm where expertise in a wider range of scientific disciplines was available. The two partners of Michael Burnside who now became partners in UDL were Anthony Wood, a Cambridge physics graduate with long experience of private practice, and Laurence Ben-Nathan, an engineering graduate of London University with extensive experience in both industrial and private practice. Also joining UDL from the Burnside firm was Roy Marsh, now in charge at the Milton Keynes office.

This short history has been completed in 1991, and there may well have been further developments by the time this history reaches a reader. Indeed the history of this or any other firm of patent agents must be one of continuous change and adjustment to changing economic conditions, changing legislation both domestic and international and the changing demands of their clients.

British patent agents have been particularly successful in meeting the demands of the European patent system and the procedural complexities of the Patent Co-operation Treaty. But equally great changes are even now in the making; the Community patent, the Community trade mark, and the Community design law are all on the way. All these will co-exist with national laws and will present applicants with a bewildering range of possibilities and they will look to their patent agents to find their way through them. Nor are the concepts of intellectual property at a standstill; new types of protection for specific purposes such as semi-conductor topographies and computer programs will also have to be thoroughly mastered. There can be no ideal formula for the size of a firm, the scale of the services which it offers in terms of different and specialised scientific disciplines, or its geographical spread. In the case of UDL, one can only observe that so far the firm has evolved and grown to the point where it seems well poised to meet the challenges of the 1990s and beyond, and that there is every reason to suppose that it will continue to do so - because in the end the success and prosperity of the firm will depend on the people who run it and who staff it, and if they continue to be persons of skill and probity, the future can be faced with confidence.

PART IV - BILL URQUHART-DYKES BY PETER LORD

For an outside view of Bill's personality and professional ability, reference can be made to the various tributes paid to him by friends and colleagues on the occasion of his fiftieth anniversary as a patent agent, also to his obituaries.

Speaking personally, after forty-seven years of close friendship, I can say that he was a true and unshakeable friend, a skilful teacher who taught by example and encouragement; a dedicated professional and a perfectionist but never finicking. He was a quiet man but behind that quietness was a person of great strength and reliability. He had a huge sense of fun and a quick wit, sometimes concealed by the reticence of a Scot. He was extremely modest, one QC once saying to him, in my hearing, 'Bill, why are you always so bloody humble?!!' which quite surprised him. He had a strong temper, always under control and any rebukes - very seldom needed or issued, were icy cold and terse. He had no enemies and bore no malice.

His probity can be illustrated by one example. One of our clients had just been taken over by a larger group. The group decided to adopt a particular word as a trade mark for part of our clients' range of products and their managing director sent a 'minion' to Bill with the instructions that this mark would be adopted and introduced after the forthcoming AGM. Bill was 'to Register it immediately.' After a quick search Bill reported that the same mark was already registered for the same goods by another much smaller firm, 'X' Ltd. He was told, 'that doesn't bother us - we'll just swamp them by television commercials and advertising'. Bill's response was to refuse to act in that matter any further. Not perhaps in the best interests of the group client, but the action of a man of total honesty who would not condone bullying by big business. Bill subsequently commented to Peter, 'I wish I were free to act for 'X' (the smaller firm). I would teach that lot (the Group Board) a lesson in commercial ethics'.

Bill was a skilled draftsman, and his patent specifications were clear and concise. Later, when he turned more and more to trade marks, he was adept both at allocating his clients' goods to their correct trade mark classification and at finding the best wording to cover those goods within the class. This ability he passed on to his first trade marks assistant, Sydney Newton, who subsequently rose high in his profession in the USA.

At an early stage Bill realised that his professional duty went far beyond merely taking instructions from clients. He would carefully question those instructions and where necessary the reasons behind them and hence get to grips with the policy (or lack of it) of his client. He was at his best when engaged in what he called corporate trade mark planning; where for example a group wished to enhance its corporate image by utilising or extending its group name or symbol (logo in modern parlance) to cover ever widening ranges of goods as business expanded. He took almost a personal pride in his clients' trade marks and was swift to warn of instances of misuse or neglect.

In contentious matters he was persistent, wise and skilful, ingenious without being crafty. He knew when to stand firm or to give ground. Cases which he argued before the Trade Marks Registrar were usually successful he refused to allow clients to pursue lost causes. His preparation of cases to Counsel were always meticulous and the barristers reciprocated by giving him their best attention in matters great and small.

Peter Lord

It is difficult to view one's own career from outside. I found the profession fascinating from the start because it offered such a wide variety of interest. Not being technically qualified (holding no engineering degree) I had inherited both artistic and manual ability from my father and grandfather. This and architectural training gave me the ability to understand drawings, and more important to be able to sketch out ideas roughly when talking to clients. My early classical education also gave me a feeling for the English language which was both helpful in finding the correct word or phrase when drafting patent specifications, and also when considering possible trade mark suggestions, when clients would produce allegedly invented words which had a horrible 'feel' to them when looked at coolly.

I too, had been trained by Bill, and to some extent by G B Ellis. The latter gave me very helpful instruction on the particular forms of legal document such as assignments, licences and agreements encountered in the profession. I developed a taste for such work, and found that frequently the examples of such documents coming before me from solicitors had been taken straight from precedents' by solicitors or their assistants who had little or no experience of patents or trade marks. Documents of this kind require not only careful scrutiny, but any criticism must be tendered with tact and discretion. There is only one thing 'worse' than criticising an inventor's 'brain child'; that is criticising a solicitor's choice of language in a draft.

From Bill, I learnt, early on, to look for the policy behind the instructions I was given by clients. If it were sound, then I could endorse it: if not, I could attempt to influence it by advice and explanation.

I can honestly say that to Bill and myself, the making of money was very low in our priorities. We were friends, we enjoyed our work and each others' company. Provided we had enough to live on and to pay the staff, profit was a secondary consideration. It was only when we began to expand and take on partners, that we realised that their interests had to be considered and their future prospects ensured.

Looking back, I am not ashamed to say that I probably advised more clients not to file patent applications or to abandon them when they appeared likely to fail than I ever advised to 'press on regardless'.

Though I did relatively little trade marks work, I strongly supported Bill in his efforts to improve the status of trade mark practitioners. I was on the Council of ITMA for many years. I supported the efforts to merge ITMA with CIPA because I felt their mutual interests were important.