Welcome to Phil's Family History Website!

We start (see “General Family Tree” top right) (click on the bold text) from two John Archers of Oxford (click on the bold text) who were 19th century brewers, and the latter of whose siblings were a carrier, a brewer-turned-coal merchant, and an H.M.R.C. excise officer and Methodist local preacher who married into the Reed (paper-making) family of Devon. The Oxford Archer family was based in the 19th century in the Grandpont area of south Oxford, with a private brewery in Archer’s Yard, on the west side of St Aldates, just north of the Thames, the family residence (‘Isis House’) at one time, actually being on Folly Bridge (the ‘Grand Pont’), and the stable for a large number of the transport business’s horses likewise (later in the century) at Grandpont. The family transport business (“Archer & Co”, latterly “Archer Cowley & Co”) was strongly connected with ‘containerisation’ (at least of furniture-transport) in the age of steam railways, commencing in 1857, not long after the railway came to Oxford (with its terminus [click on ‘terminus’ to go to information about the link] at Grandpont close to Folly bridge), and ending in 1969 (by sale to Cantays) 112 years later, in the decade of the Beeching Report and the commercial end of steam on British Railways.

The marriage (of Alfred George Archer, Inland Revenue officer, to his boss Edward Reed’s daughter, Olive Emma Reed) into the Reed family also provided a link to GJ Churchward, almost the GWR’s most famous son and Chief Engineer (1902-1921), whose creation of the GWR's “Stars” and “Saints” laid the foundations of much of the UK’s 20th century’s steam engine design. The family transport business followed-suit after the Oxford GWR station moved from Grandpont to Botley Road. Archer Cowley moved its head office from Pembroke Street to Park End Street, building in 1901 a monumental warehouse facade which remains to this day. Some of the descendants (including me) of those two 'John Archers of Oxford’ (with whom we started above), found, from the mid-1920s to the latter 1950s, a sort of 'promised land or golden country' at William Archer’s inherited ‘country seat’ at Somerville (click on the bold text), 130 Banbury Road, Oxford. That ‘golden country’ at Somerville has to some exent provided an inspiration for this web-site, and for related latter-day family ’Somervilles’ in Rutland, St Helier’s New Zealand, and Rowlands Gill, Tyne & Wear, referred-to herein, variously as ‘Somersday’ and ‘Somersday II’ and so on.

The Reed family link mentioned above, provided by Alfred George Archer’s marriage to Olive Emma Reed, served also to connect the Archers to the entrepreneurial side of the Reeds, exemplified by Olive Emma’s brother Albert Edwin, founder of the Reed Paper empire, in whose paper mill at Raamsdonksveer in Holland William George Reed (my grandfather, ‘WGRA’) worked from 1894 to 1900 when he returned to Oxford and married (in 1902) into the Gilder family of Jericho, Oxford, who had then recently moved to Hinckley, to continue working in the textile field there.

Related families (to the above Archers of Oxford) include the Gilders of Oxford who were 19th century tailors (click on the bold text), the Reeds of Somerset and Devon, who were 19th century millers and entrepreneurs, the Reeds’ Devonshire neighbours the Churchwards who included the GWR’s one-and-only ‘G.J. Churchward’, the Penfolds and Wells of Surrey, who were 19th century, gardeners and Chrysanthemum-growers, auctioneers and latterly estate agents, the Garners of Middleton and Radcliffe, with forebears in the Lancashire cotton-industry, and many other families of course. Geographically, the family links Oxford districts such as Grandpont, St Aldates, Walton Street, Jericho, Tackley Place, Banbury Road, North Oxford and Headington, with London’s Southwark and Surbiton, Lancashire’s Prestwich, Whitefield, Radcliffe and Middleton, not to mention Somerset’s Stogursey. This 'work-in-hand’ site will never be ‘complete’. It is a heady mix of genes and experience, finding inspiration and aspiration in a gamut of lives from agricultural labourers, aviators and academics through furniture-removers, racing drivers and railway engineers, to washer-women, wood-engravers and Lancashire cotton-mill-overlookers…..and not forgetting Bedlington terriers and blackbirds….'yeah that complex mix that is life itself!'

The intention is to make available, completely non-commercially, and on a ‘private study’ basis, to those half-a-dozen or so family members to whom, if anyone, it may be of interest, this 'colourful tapestry' or, you may say 'scrap-book', of life in Oxford and South-London, and many other places, over the last two-hundred or so years. Possibly it may link the members of this disparate family group, in a way not previously attempted. In my dreams I see the tapestry as forging an identity for the group, and becoming, in a way, its talisman. Wiring together lives in Oxford’s Jericho and London’s Southwark, or Surrey’s Merstham and Lancashire’s Middleton almost as effortlessly as the genes have done, is my delight. Not just a fantasy, I hope. But equally I'm not claiming rigour in my research. There will be many shortcomings, errors, inaccuracies, and inconsistencies. I know. Email me, please, if you have time, about important errors or omissions or new information that I should be aware of. I will do my best to attend to them as soon as possible. Over time they will be corrected. The basis for comparision is that this information, or some of it anyway, has not hitherto been readily available at all. For example, my grandpa William Archer, splendid man that he was, wrote the history of Archer Cowley & Co (click on the bold text) on the back of a small envelope (which envelope I am very pleased to say I have in my records), and the wonderful (so I believe, though I never saw it, nor was it ever mentioned in famiy discussions) illustrated history scrapbook of the firm was passed to Cantays who took over the Archer Cowley & Co business in the 1960s, without copying (as far as I can tell) any of it for the Archer family, and Cantays have lost it “in an office move”. End of story. Until now. So much to do! (Update: 26.12.17): the scrapbook was recovered in July 2016 and now features prominently in this site: click here to go to it).

(Added 4.4.15): To quote my elder brother Michael Archer, verbatim about this website, and from the first year of its existence: ”It is definitely the place to unravel how generations of The (rather less famous) Archers fit together.” - which, coming from Michael, I take as a compliment.

The Archer Cowley window (please click on the thumbnail). Cantays very kindly alllowed me to photograph the window in 2006.

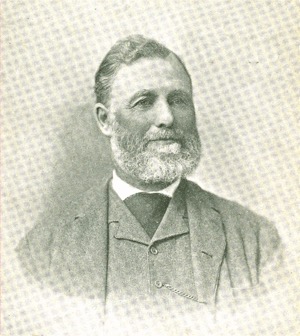

Instances of achievement in the family include GJ Churchward, the locomotive engineer of the Great Western Railway from 1900 to 1922, though he is not a blood relative, but only a relation by marriage. Another is Gwenda Morgan (click on the bold text), my mother Gwen Archer's first cousin, who became well-known as a wood-engraver and whose very characteristic work is widely available through the internet under her name. Ann Archer Archer, probably completely unknown outside the family, who lived for many years with her brother Thomas in Adelaide Street, Jericho (click on “Adelaide Street” to go to its map) has left us a wonderful sample of her appliqué skill - a bedspread beautifully decorated with images including at least one current event of the time namely hot-air ballooning. Lizzie Gilder, wife of William Archer, is another family artist, whose “At Oxford’,a view of Oxford castle (signed “LG”, for Lizzie Gilder) is seen below on this page. Another achiever was William Wells the chrysanthemum-grower-and-international exhibitor and founder of the firm Wells of Merstham, Surrey. And several others - not least, Gwen Penfold, my mother, herself, whose piano-playing (click here for more about her ‘Hausmusik’) brought such joy to all who heard her, and in particular her three sons who grew up knowing every note and phrase and nuance of such challenging piano works as Chopin's Ballade No.1 in G minor and his posthumous Fantasie impromptu, the Debussy Arabesques and Claire de lune, Ibert’s 'Little White Donkey’, and most of the Chopin Études, to name but a few. Gwen’s younger brother Raymond Penfold, wartime radar boffin, radio amateur and hero of my youthful days is another whose story needs to be told. And of course there is James Archer, who founded in 1857 at the age of 21 (and probably borrowing his father John Archer’s brewery horse and cart for the purpose) the transport business which became “Arher Cowley & Co” whose early twentieth century letter-head is shown as the banner (above) for the pages of this website.

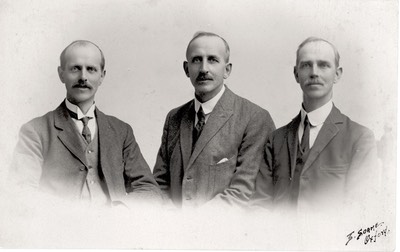

Ernest Archer, elder brother of William Archer the owner of Somerville, is another member of the family whose life lends colour to this chronicle. In 1912 he became an aviator, constructing a bamboo-based aircraft frame, powered by a motor-cyle engine (**) and gained his pilot’s licence from the then-dominant French aviation authority and flew his aircraft in his adopted home-country, Holland, at Twello, well before the outbreak of The Great War of 1914-1918. Ernest made a career in the sales side of the automotive industry, abandoning his apparently intended metier of paper-making with his (by then) successful Uncle Albert Edwin Reed (his mother’s brother) at Raamsdonksveer in Holland, as indeed did his brother William who had likewise spent some years learning that business and the language in the Netherlands. William’s eldest son Arthur (my ‘Uncle Arthur’) perhaps adopted his Uncle Ernest as a childhood hero, as Arthur’s initially-chosen career path was likewise ‘automotive-based’ in that he worked for the Oxford firm of Morris Motors in the test department and drove a ‘works-entered’ supercharged MG in the Monte Carlo Rally at least once and achieving very creditable results.

(**): text in light oblique now thought to be not strictly accurate - see corrections in pages about Ernest Archer.(pba.3.11.14).

Oxford itself, the home of my youth, the brewery in St Aldates, Oxford run by my 19th century ancestors, Port Meadow, Oxford, where the ‘golden afternoons’ of my youth were spent fishing and swimming, the paper-making factory at Raamsdonksveer where my ‘Reed’ forebear Albert Edwin established one of his many businesses, and his nephews Ernest and William came to learn about it, rowing on the Isis, railways around Oxford and elsewhere - these are all chosen highlights from the mixture of the mundane and routine events in many lives, which I will try to illustrate in due course.

Seek esewhere a celebration of wealth, conventional status and influence, and a hierarchical society, though there are one or two examples in the family. This site rejoices in life itself (click here for a page on ‘Life Itself’) and its 'ceaseless round' and variety, and the colourful tapestry it weaves around us all. Perhaps I am trying to weave facts and people into such a tapestry. A tapestry recording parts of many life-journeys. A tapestry of family culture. A mute inglorious Milton perhaps this family has. Gwenda Morgan, herself very much of a retiring disposition, certainly did justice to him in her beautiful Golden Cockerell Press edition of Grey's Elegy. Possibly we have a guiltless Cromwell, who knows? Some involvement, certainly, in administration at a local Rutland level in the first decade of the 21st Century. At least some instances, I trust and believe, of Dorothea Brooke's example of a life whose effect was "incalculably diffusive: the growing good of the world being partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs". But perhaps this website may do a little to shine some virtual light on those lives and into those peaceful tombs. If so, one of my life's lattermost great tasks will be accomplished.

And in this site I will try not to overlook that the short period in which the lives of those mentioned here occurred is indeed but a blink of an eyelid in the context of ‘life on this earth’. And this is even likewise true to a degree in the context of the lives of our nameless iron-age and earlier forebears whose traces can be visited, for example, at the hill fort at Burrough on the Hill, Leicestershire. Those lives are relatively so obscure to us, but certainly so different from ours, not least in respect of the daily threat of plunder from fellow-countrymen seeking an easier living than was to be had from tilling the soil.

A taste of family memorabilia. Here is my grandma Lizzie’s rendering of a quiet corner of Oxford in (I think) her young days. Please click on the thumbnail:

“At Oxford” (undated) by “LG”, Lizzie Gilder, currently in the possession of Michael J. Archer, my elder brother. Elizabeth Emma (‘Lizzie’) Gilder was the wife of William George Reed Archer. Oxford castle, which is now the Malmaison Hotel, is visible in the background. It seems likely to have been drawn by Grandma Lizzie before she married in 1902. Perhaps it was done during the years that her husband-to-be, William Archer, was in Holland (about 1894 - 1900) when she was a teenager living in Mr George Blake (the house-furnisher of Little Clarendon Street)’s household, as his adopted daughter, after her mother (sister of Mr Blake’s wife) died when Lizzie was about 7 in 1883, and the rest of Lizzie’s family had left Oxford to start a new life in Hinckley, Leicestershire.

European Wars: (added 25.11.16)

And their elimination by the Iron and Steel Community / The Europeand Community / The European Union following the end of World War II in 1945:

Family connections with European Wars:

1) The family name: Archer, and the strategic use of archers in warfare before and after Crecy and Agincourt. The longbow was the ‘machine gun’ or ‘mitrailleuse’ of the Middle Ages. Archers were cheap to employ (in terms of daily pay), and were expendable, and used in very large numbers, and thus were killed in very large numbers, in European wars during the Middle Ages;

2) World War 1 of 1914 - 1918 also known at the time as ‘The Great War’:

The family lost Percy Gilder, half brother of my paternal grandmother, Elizabeth Emma Gilder, my paternal grandfather, William GR Archer’s first wife. Percy Gilder was killed in the battle of the Somme (July to November 1916), along with 1,000,000 other combatants and civilians in that titanic and meaningless struggle. I have details of Percy Gilder’s involvement in that battle and will provide a link (here) to those details as soon as I can do the page to link to this paragraph;

The family was involved in ‘air-raid-response-work’ in the sense that my maternal grandfather, Frank Penfold, my mother Gwen Penfold’s father, was an air-raid warden in The Great War 1914 - 1918 in London, responding to the damage and injuries caused by German Zeppelin and Gotha bomber raids. These were, according to my mother, who was aged 5 to 9 during that war, much more significant than seems ever to be acknowledged in documentaries of that war. Much damage and many injuries and corresponding terror and anxiety were caused in London by these raids; and the family eventually moved from Willesden to Brighton to escape the horror of these nightly events;

The thunder of the guns from the battlefields in France could be heard on the south coast during this war. My mother Gwen Penfold.Archer spoke of this in terms of a an ominous background rumble affecting life itself and spreading alarm and despondency as the years of the apparently never-ending war (that was going to be ‘over by Christmas 1914’) advanced. And as those years ground-by, so the consequences of the war became apparent, not least in providing stark visual evidence of the horrific injuries that the front-line fighting could cause, in cases where the merciful release of death (reported by telegram whereby telegram-delivery became like a potential death-notice) was not forthcoming. My mother’s family, the Penfolds, lived at Brighton during part of the war and there was a hospital nearby for the treatment of the wounded from the battlefields. Those patients who reached a state where they could walk about would be seen in the strikingly prominent hospital blue uniform which attracted attention to their very presence there, and thus drew the gaze of residents and passers-by to their war-wounds and disfigurements. These latter, one would have thought, would have been seen as ‘badges of honour’ distinguishing these ‘brave citizens who had heeded the call-to-arms, and offered in service of their nation their very lives and limbs’. However, such was by no means a universal reaction to such disturbing sights as ‘Mr No-nose’, who terrified my mother and her brother in Brighton, during those war years, in the days before restorative surgery was even contemplated, and in their own wasy caused a deep-seated sense of the horror of war that was passed on to the next generation - my generation.

The dark impenetrable deadly-horror conveyed by the name “The Somme” has been an accompaniment to my life since its meaning percolated through to my senses as a young person in the 1940s and 1950s. A battle in which 1,000,000 souls perished in an attempt to change the termporary occupation of a few miles of French countryside during just over 4 months, commencing on 1st July 1916, when my mother was 6 days short of 7 years old. The battle in which all the German defences were supposed to be destroyed by a week-long barrage of a million shells from the British artillery. But they weren’t destroyed because the Germans had dug-in deeper than was assumed, and as soon as the barrage lifted, it was obvious that an attack was coming, and the machine-gunners had lots of time to exit their dugouts and to set up their deadly lightweight machines to mow-down the strolling British battalions who were confident of meeting no opposition whatever.

The names “Somme” and “Zeebrugge” were given to two ‘Director’ class 4-4-0 steam locomotives, to commemorate aspects of the WW1 struggle. And one day in the 1950s these two engines came through Oxford on (I think) a Stevenson Locomotive Society special train, that was widely-anticipated and celebrated by the train-spotting fraternity. But it was not seen by me, sadly. How I missed it, I will never know. But I did. Nevertheless, for me, the significance of those names rings down the decades since like an omen. In the 1940s and 1950s, the Somme was only 30 to 40 years back, Now it is exactly 100 years back, but the incubus that it represents has still the power that it ever had. For me. For the generation that knew its meaning second hand - as opposed to very indirectly. The exittence of those specially-named engines was all part of the security that seemed to have been built-up since WW2, including the Iron & Steel Community, the Armisitce celebration on November 11th every year. And other such safeguards which all said: “This shall never happen again”