(This text is transcribed from a copy of the 1999 text of this publication, commencing 1.9.2014, and graphics will be scanned and added, so the transcribed book will ‘grow’ as time passes) pba.1.9.14.

Reminiscences

By Capt William Urquhart Dykes R. F. C

Reminiscences of a pilot flying with the Royal flying Corps over the Ypres salient (R. E. 8s) in 1917 and with the Royal Air Force in 1918 in what is now the Irish Republic (R.E.8s and Bristol Fighters).

Contents:

Cover photo: RE8 on patrol;

Frontispiece: the author in his racing heyday;

Introduction: by Peter Lord;

List of headings separating sections of the text, with page numbers of the 1999-published booklet:

- How it all started (page 1);

- My initial training (page 3);

- My first solo (page 4);

- More advanced training (page 6);

- To France (page 7);

- Introduction to the front line and reconnaissance (page 10);

- Photography work. Non-official fighter escorts (page 13);

- The clock code for reporting to our battery where shells landed (page 15);

- Resident signal staff at own battery site (page 17);

(List of headings to be continued in due course after dictating the text of the above pages)

Introduction

By Peter Lord

Reminiscences of pilots of the Royal Flying Corps in the 1914-1918 war have mainly dealt with memories of those who flew scouts (fighters) or bomber aircraft. Few have covered the important work of reconnaissance or artillery observation, which entailed flying unarmed or lightly armed two seat machines such as the BE2 or RE8 at relatively low altitude and slow speeds.

Captain William Urquhart Dykes - Bill Urquhart Dykes to his family and friends, did not think of recording his experiences until he had retired from his profession as a Chartered Patent Agent in the early 1970s. Then with the help of his pilots log book he set down his memories of the years 1917 to 1919 as a young pilot.

Bill, my friend and professional partner, whom I knew closely for some 38 years, was astonishingly modest. When he could be led to talk of his experiences, he never mentioned danger or fear. He would recall his aircraft with an affection-mainly the RE8 or the Bristol Fighter - but never thought to mention that neither the pilot nor the observer were issued with parachutes. He became a Captainin R.F.C and Flight Commander at the age of 19, and he was loved and respected by his brother Officers and men.

The bulk of Bill’s operational flying over the Ypres salient in 1917 and 1918 was in the RE8, an aircraft with the reputation of being difficult at least to inexperienced pilots. It was unstable unless carrying a passeng, or failing that, ballast the rear cockp. When spotting for 9.5 howitzer, the pilot had to fly steadily and relatively slowly at low altitude, to enable the gunners performance to be monitored and photographed or transmitted back by radio. Bill said that at 3000 to 4000 feet, one could frequently observe shells in flight from either combatant, at the top of their trajectory.

Bill flew some 300 hours over the Ypres Salient in 7 and 9 Squadrons, without crashing; and then in the West of Ireland with 105 Squadron. Over the Ypres salient it was RE8s, and in Ireland he flew them for some 150 hours before being issued with the far more airworthy Bristol Fighter, one of the finest of the World War I aircraft. He only had one dangerous force landing, when the engine of his Bristol failed while he was crossing Lough Corrib. He managed to force land safely on a hillside at the edge of the Lough.

He did not fly in the 1939-45 war but rejoined the R.A.F as an Engineer Officer. He insisted (against Kings Regulations) on wearing his RFC Wings, and his various Commanding Officers were only too glad to allow this.

Bill was a careful and skilled pilot with a sympathy for his airframe and engine. This ability stood him in good stead when between the wars he maintained and drove his own Alvis car in competitions and also drove in the official Alvis works team, at Brooklands, Le Mans, and in the first Ulster T. T.

My abiding memory is of a very modest, but highly skilled man with an outstanding ability to pass on his knowledge and inspire those who worked with or for him. Beneath a quiet Scottish exterior there dwelt a generous, kindly and warm and nature, which endeared him to all who knew him well.

(Signed): Peter Lord.

Reminiscences

How it all started

I wanted to join the Royal Flying Corps as a pilot and I pondered how to free myself from my parental clutches, my only living parent being my mother, who thought that aircraft were dangerous beasts. I could not convince her otherwise. Also I had to evade the clutches of Colonel Louard, who was then commanding the 3rd Battalion of the Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) at Nigg in the North of Scotland. Not only had I accepted a commission in that battalion because my father had been a regular officer in the 26th Battalion of the Cameronians, but he had been a personal friend of Colonel Louard. Unfortunately my father died in 1911.

My Colonel was none too pleased to lose one of his young officers, because he had spent much time and trouble in training me by sending me on a long musketry course at Strensall, also on courses dealing with (ground) Lewis Machine Guns. Although I say it myself, I got very high marks both that the Strensall Musketry course and at the Machine Gun courses. Hence, it was with considerable reluctance that I was sent off to Cromarty for a Medical Board; this being the nearest Board to Nigg Camp. This was rather a “one horse” outfit comprising a small hut, a charming old Medical Officer, one R.M.C orderly and the normal gear, not forgetting the usual eye chart hanging on the wall.

I passed my medical test with flying colours, but crashed badly at the last line on the eye test. To this day I remember how it ran. It read:

A P X UZ

The M.O. Enquired if I had been reading late the night before and I told a bad lie and confess to having read a fascinating detective novel until midnight. He obviously wanted me to pass and invited me to return the next day for another try. Before leaving the heart, I was able to read:

A P X U Z forwards and Z U X P A backwards.

Five bob to the medical orderly ensure that the chart was not reversed. Next AI secured a 100% pass, but the sequel, which took place in the Ypres Salient, nearly landed me in trouble.

Officers were not transferred from their regiments at that time; they were “seconded” to the R.F.C, retaining their rank at the date of seconding. Hence I started as a 2nd Lieutenant. One could either wear the uniform of one’s regiment, in my case khaki tunic and tartan trews, or one could wear the double-breasted khaki coloured tunic, popularly known as a maternity jacket. When we felt like it, we sometimes mixed the two. At times I wore my Glengarry and at times an R.F.C cap.

(Added 01.01.2014): Text of pages 1-20 pasted from QuarkXpress-format file:

REMINISCENCES

How it all started

I wanted to join the Royal Flying Corps as a pilot and I pondered how to free myself from my parental clutches, my only living parent being my mother, who thought that aircraft were dangerous beasts. I could not convince her otherwise.

Also I had to evade the clutches of Colonel Louard, who was then commanding the 3rd Battalion of The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) at Nigg in the North of Scotland. Not only had I accepted a commission in that battalion because my father had been a regular officer in the 26th Battalion of the Cameronians, but he had been a personal friend of Col. Louard. Unfortunately my father died in 1911.

My Colonel was none too pleased to lose one of his young officers, because he had spent much time and trouble in training me by sending me on a long musketry course at Strensall, also on courses dealing with (ground) Vickers and (ground) Lewis Machine Guns. Although I say it myself, I got very high marks both at the Strensall Musketry course and at the Machine Gun courses. Hence, it was with considerable reluctance that I was sent off to Cromarty for a Medical Board; this being the nearest Board to Nigg Camp. This was rather a “one horse” outfit comprising a small hut, a charming old Medical Officer, one R.M.C. orderly and the normal gear, not forgetting the usual eye chart hanging on the wall.

I passed my medical test with flying colours, but crashed badly at the last line on the eye test. To this day I remember how it ran. It read:-

APXUZ

Page 1

The M.O. enquired if I had been reading late the night before and I told a bad lie and confessed to having read a fascinating detective novel until midnight. He obviously wanted me to pass and invited me to return the next day for another try. Before leaving the hut, I was able to read:-

A P X U Z forwards and Z U X P A backwards.

Five bob to the medical orderly ensured that the chart was not reversed. Next day I secured a 100% pass, but the sequel, which took place in the Ypres Salient, nearly landed me in trouble.

Officers were not transferred from their regiments at that time; they were “seconded” to the R.F.C., retaining their rank at the date of seconding. Hence I started as a 2nd Lieutenant. One could either wear the uniform of one’s regiment, in my case khaki tunic and tartan trews, or one could wear the double-breasted khaki coloured tunic, popularly known as a maternity jacket. When we felt like it, we sometimes mixed the two. At times I wore my Glengarry and at times an R.F.C. cap.

Page 2.

My initial training

My first flight ever was at Turnhouse (Edinburgh) where I was taken up in a Maurice Farman Longhorn. By way of initiation, my instructor took a savage delight in diving in a diagonal direction under the main telephone cables, which ran across the western end of Prince’s Street, Edinburgh. I stress the diagonal run because only in this direction could he get enough length of run to achieve this feat of lunacy. I gather he had one - or possibly several - girlfriends to impress, but in the possible but unlikely event that he is still alive I refrain from mentioning his name. He repeated his act in a Maurice Farman Shorthorn. You had only to observe the very poor factor of reliability of these engines to wonder that I am still alive to tell the tale.

Both Maurice Farmans were the very devil for swinging on take off and one needed full rudder and quick throttle opening to keep on “the straight and narrow”, coupled with the luck not to choke the engine!

Page 3.

My first solo

I did my dreaded first solo flight on Saturday 31st March 1917, and, as I feared, the Shorthorn swung like hell on take off. The aerodrome flagstaff and wind-sock seemed to have quite a magnetic attraction. I only cleared the flagstaff by less than six feet and looking over the side saw a starting up competition between the respective drivers of a Model T Ford ambulance and a Crossley Fire tender. I later learnt that both drivers were just as scared as I was.

While we were pupils, we wore heavy crash helmets, which we were allowed to discard when we had passed out and got our “R.F.C. Wings”.

I left Turnhouse after a total of five hours and five minutes solo flying.

Next I moved to Cramlington, near Newcastle, where I started on Avros, with Gnome engines. The latter had very dubious valves in their pistons and gave much trouble. At the same aerodrome, I progressed to the small Armstrong Whitworth, which had an almost unbreakable sprung under-carriage. From memory, these had 90 h.p. air-cooled engines. We gave them a good testing, since we had to make two night landings after about eleven hours flying and well before I was able to fly properly by day. Incidentally, the fatal casualty rate at night was about 50% at Cramlington.

We also flew some large Armstrong Whitworths at this aerodrome which were fitted with 160 h.p. Beardmore engines. (A fine example exists at Old Warden). They were famous for their copper water jackets and positively operated pull and push valve rocker arms. The large Armstrong Whitworth had the worst forward visibility when landing that it has ever been my misfortune to encounter. At Cramlington I had a lucky escape when a large A.W. A9982, failing to see

Page 4.

where I had just landed in an Avro A 5948 out on the middle of the aerodrome, almost squashed me flat. He landed across my tail and his wing tip actually tore my leather jacket from shoulder to shoulder, leaving my tunic intact.

The impact swung his machine at right angles, so that his large A.W. landed sideways and did a lateral belly landing, which collapsed the undercarriage.

An ambulance and separate fire tender roared up to the scene only to find the A.W. pilot and myself behaving like two angry motorists on the Brighton road on a Sunday afternoon. A Cockney voice enquired “Ain’t yer ‘urt?” but on hearing our verbal battle in quite unprintable language drove off and left us.

We waited for the matter to be sorted out by an outraged flying instructor left with two unserviceable machines - one large and one small - on his hands for several days in a rather bent condition.

I went to the Equipment Officer to draw a new leather coat. He was decent enough to accept my claim that it was an “occupational hazard”. It took a week or two before my back unstiffened. Playing rugger is a better form of sport than trying conclusions with Armstrong Whitworths!

Page 5.

where I had just landed in an Avro A 5948 out on the middle of the aerodrome, almost squashed me flat. He landed across my tail and his wing tip actually tore my leather jacket from shoulder to shoulder, leaving my tunic intact.

The impact swung his machine at right angles, so that his large A.W. landed sideways and did a lateral belly landing, which collapsed the undercarriage.

An ambulance and separate fire tender roared up to the scene only to find the A.W. pilot and myself behaving like two angry motorists on the Brighton road on a Sunday afternoon. A Cockney voice enquired “Ain’t yer ‘urt?” but on hearing our verbal battle in quite unprintable language drove off and left us.

We waited for the matter to be sorted out by an outraged flying instructor left with two unserviceable machines - one large and one small - on his hands for several days in a rather bent condition.

I went to the Equipment Officer to draw a new leather coat. He was decent enough to accept my claim that it was an “occupational hazard”. It took a week or two before my back unstiffened. Playing rugger is a better form of sport than trying conclusions with Armstrong Whitworths!

Page 6.

To France

After doing four hours and five minutes solo time on these machines, I left 81 Squadron for France. My total solo flying time on arrival there was 35½ hours. I knew that I was not competent to fly, but what I did not then know was that the spring offensive of 1917 was about to start in the Ypres Salient and Passchendaele Ridge area. All pilots at that time were sent over from England by boat, either to Calais or to Dieppe. From these ports a dreary train journey (usually by night) ensued to St. Omer, which had an aerodrome on which were parked out in the open a vast array of aircraft of all kinds. These included fighters, or scouts as they were called in those days, e.g. Sopwith Pups, Sopwith triplanes, Spads and S.E.5s. In the reconnaissance, photographic and bombing class there were the B.E.2.c, B.E.2.d, B.E.2.e, R.E.8, Bristol Fighter, D.H.4 and D.H.9, the latter two being used for long range reconnaissance and photography. To keep pilots occupied at the St.Omer pool while awaiting allocation to a particular squadron near the front line, they were given the task of dismantling crashed aircraft. Each pilot was dished out with a few tools and boxes of different sizes into which to put the various bits and pieces from the wrecked fuselages. Damaged engines were not dealt with by pool pilots, since such engines were shipped back to England for overhaul by the respective makers or subcontractors. The job was a dull one, but grim at times, since occasionally one came across bits of human flesh or hair, sticking to the fuselage. I did not have more than a week to wait at the pool, when a Crossley tender arrived from No.7 Squadron, and took me and my personal kit, together with my flying gear to Proven Aerodrome, near Poperinghe (west of Ypres in Belgium, Ed). It was quite a long drive, but my driver regaled me with interesting stories on the way and

Page 7.

seemed to know the road well. The trip was a slow one, due to heavy two-way traffic, including troops on the march and the tractor haulage of heavy guns, likewise teams of horses pulling lighter artillery.

When I arrived at Proven, I was taken to my hut to dump all my gear. I was then shown to the offices of the Adjutant and the Squadron Commander, to whom I was introduced and my particulars taken in great detail. After being issued with appropriate maps of the area, I went to see the three Bessoneaux hangars, one for each Flight, also huts housing armourers dealing with machine guns and bombs as well as several huts for a very large photography section.

The Squadron was in the process of changing over from B.E.2.es to R.E.8s and on the following day, I was ordered to fetch a new R.E.8 from the St. Omer pool where I was taken by the same driver who had brought me on the previous day. After dealing with the necessary paper work, a brand new R.E.8 was produced and started up. Having run the engine up on the chocs and found it was giving its full revs. on each magneto (about 1500 to 1600 r.p.m.), I waved away the chocs and taxied off to my correct take-off point.

I was not accompanied by any mechanics to the point, so having looked around to make sure that no other aircraft was landing or about to take off I opened up and took off. I circled around the aerodrome to get my general direction and lie of the land, when I was dismayed to notice that the Airspeed Indicator (A.S.I. for short) was grossly under-reading and indicating only about 40 m.p.h. at which speed the machine would, of course, have been stalling. As I had full control thereof and, by its feel, I knew its speed was more like 80 m.p.h., I decided to reject this R.E.8 as being unserviceable. St. Omer aerodrome was at least three or four times as large as Proven aerodrome. I knew that I had not the experience to

Page 8.

land at Proven with a defective A.S.I. As it was, in landing again at St. Omer I used up most of the aerodrome in so doing. After more paper work, I was issued with another R.E.8, in which I flew back to Proven without trouble. This was my first landing ever at Proven; I was very glad that I did not attempt it in the first machine, with the dud A.S.I., issued to me by St. Omer.

Proven aerodrome was rectangular in shape and housed two Squadrons at opposite corners of the rectangle. No.9 Squadron (to which I later moved, on promotion to Captain) was at the other corner.

Page 9.

Introduction to the front line and reconnaissance

On Thursday 5th July 1917, I did my first line patrol. It was usual to give a “raw” pilot like myself an experienced observer. I felt sorry for these chaps, because they did not know if the “new boy” pilot could even take off, fly or even safely land an R.E.8. I soon realised that some of its bad reputation had gone overseas before me. Before taking off on a reconnaissance flight for Artillery Observation purposes (always spoken of as “Art Obs.” for short), the first thing to be done was to call at the Squadron Office of the Artillery Intelligence Officer. He would hand to me and to my observer a special map each, which was printed weekly by Army Corps Headquarters, who had their own map printing press at a safe distance behind the lines. Its location was kept very “hush-hush”. This map was printed every Sunday night and showed all German batteries with their numbered positions as known up to the close of Art. Obs. on the preceding Saturday. The map was compiled from a mosaic of the photographs taken by all the Squadrons operating in the Corps area. To this were added the totality of the gun flashes spotted by all the pilots and observers flying over that area and reported to the various Intelligence Officers of the Squadrons concerned.

It was the aim of every Squadron to deal with all those numbered batteries by Art. Obs. for our own batteries enabling them to pulverise the enemy batteries out of existence by the close of Art. Obs. on Saturday evening. This allowed Corps H.Q. to have new maps ready for distribution on the Monday morning. These new maps had fresh numbers of German batteries for next week’s job. One can imagine that the preparation of these weekly maps entailed vast co-ordination and much hard work on the part of all concerned therewith.

Page 10.

With the above map, the Squadron Intelligence Officer always lent me a stopwatch (which I hung on a cord round my neck) at the same time telling me the approximate time of flight of the shell of the battery for whom I was observing on that particular day. Assume it was, say, twelve seconds. My own personal code letter was “D” (each pilot had personal code letters) and I would send down by Morse code a signal to our battery reading “D GG GG” (the letters GG were an abbreviation for GO GO or Fire Fire). It was usual to repeat each signal twice.

Having sent them the signal to fire, I would await the gun flash, pressing my stop watch the moment I saw it. At the same time I would turn towards the German battery site to look for the shell burst, which I would see at the expiry of twelve seconds. We carried enough petrol in our main tank to remain airborne for about three hours. Our reserve tanks we sealed off and disconnected from the fuel system, but we did partially fill them with Pyrene as a precaution against fire in the event of a crash landing. After finishing a “shoot” we sent down to our own battery the signal “CI patrol” before turning for home. Since our signal strength was relatively weak and highly directional, it was essential to transmit only when flying towards or over the top of the battery.

While flying back to base, a good observer would first wind in the aerial and then start making out his report for the Artillery Intelligence Officer. This would include his flash spottings of any German batteries. Having landed and taxied up to our Flight hangar, I reported any fault noticed with the engine or rigging to the appropriate engine fitter or airframe fitter. Other mechanics filled the main tank with petrol which was always put in through a chamois leather filter. The engine fitter also filled up with oil.

By this time my Observer would have reached the Artillery

Page 11.

Intelligence Officer and be handing in his report and I would follow and do likewise. He would question us closely, asking if German battery number so and so was seen to be active. He would ask us about other points of interest, for example had we seen any railway train movement and, if so, where? Had we had trouble with enemy aircraft? Or with German “Archie”? (The term used for anti-aircraft shell fire of either side.)

Page 12.

Photography work

Non-official fighter escorts

During the 1917 spring offensive, photography over the German lines was required on an ever increasing scale. To enable us to carry this out properly, we badly needed a fighter escort over us at about 12,000 feet, in order to let us fly straight and level at about 12,000 feet over, and parallel to, the main German battery area. Our fighters were much too busy carrying out their offensive patrols far over the line to be diverted from what was really their main task. Accordingly we arranged unofficial fighter escorts with a Squadron of Sopwiths, S.E.5.a.s or Spads, by inviting one or more of them to a “binge” at our Squadron mess on the night before we intended to carry out our photographic mission. The Squadron Commanders of these fighters used to invite us to a rendezvous at, for example, 10,000 feet over their own aerodrome at, say 11.00 a.m., but pointing out that we must be at the agreed height very punctually, as they would not keep a whole fighter squadron waiting for one lone R.E.8.

My observer and I made a special point of starting off early for the agreed fighter aerodrome, which was about two miles away, climbing hard at full throttle as we went. We used to look over the side of our machine when we attained an altitude of about 9,000 feet, when one saw the fighters were still on their aerodrome. We had misgivings that they were not going to keep their date with us. However, we circled round for quite a short while, when low and behold up they came, looking just like a swarm of midges as they shot up above us to about 12,000 feet, when the leader fired a Very pistol, as the agreed signal to follow him. It was wonderful to see this horde of scouts over the top of us and spread out into a perfect formation as we all made for the front line. They stayed

Page 13.

overhead long enough to let us make one run up and one run down our area to be photographed. In other words we took two lines of vertical pictures, each of which overlapped its neighbour. Not only were we free from disturbance by enemy aircraft, but there were so many of our own machines spread above us that the German Archie dispersed their fire with considerable loss of effect.

I found that when no escort was available to distract Archie, he made things quite hot for us. When taking vertical photos, one must fly the machine very level in order to get a good picture. From the time the German Archie battery had fired, his shell took very roughly ten seconds to reach us, so that if we continued on a level course and at the same height, he would rapidly find his range on us. I found it a good plan to sideslip every eight seconds, say to the left and before ten seconds have elapsed sideslip to the right, each sideslip being interspersed with a period of level flight, during which I took my picture. It was not easy from the ground for Archie to tell whether the machine was sideslipping or not. You could play a game with him and tease him, which often used to cause Archie to make a double correction. Hence it paid to vary one’s tactics from time to time, otherwise he would get you!

Page 14.

The clock code for reporting to our battery where shells landed

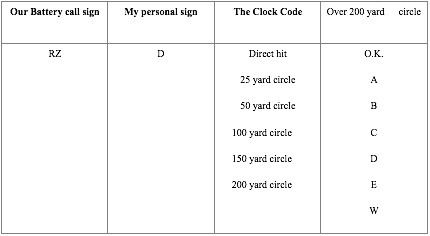

It was my job to tell our Battery Commander where his shell had landed, which I did by using “The Clock Code”. This entailed holding a notional or imaginary clock with 12 o’clock always facing north and its centre on the enemy battery site. Our own battery had its own code signal, for example, RZ and each pilot had his personal code signal, mine being D. I set out below in tabular form the signals for the Clock Code:

Page 15.

If (which was very rare) the enemy battery had suffered a direct hit, the signal (repeated twice) would read “RZ D 12 OK”.

Assume, which was more likely, that our own battery’s first ranging shot had fallen 200 yards to the south-east of the enemy battery site, my signal would have read “RZ D E 4”. I would have varied my signals in accordance with the above table, until our Battery Commander had ranged all his guns within the A circle. When and so long as he maintained that degree of accuracy, I would continue to cruise backwards and forwards between the two respective batteries, taking the opportunity while over the enemy battery to drop my four 20lb bombs. An aerial photograph dated 11 Sept 1917 is marked with the sites of 3 German batteries accordingly.

If I saw my own battery was letting its guns go outside the A circle, then I would send down further correcting signals.

Page 16.

Resident signal staff at own battery site

Our Squadron maintained its own Signal Staff at each English battery with which we worked, such staff being, so to speak, “resident” at the battery site. They were in field telephonic contact with our own Artillery Intelligence Officer. His job included telling the Signal Staff when our own machine had taken off for the line.

I had first to establish contact with the battery to make sure that it was receiving the signal to fire. If it got the message, the Signal Staff laid out a large white strip bearing the letter K on the ground. If I got no reply to repeated sending of the letters “GG”, there were two possible reasons. First that enemy aircraft were overhead either taking photographs or making visual observation. If that was the case, the battery commander would withhold displaying the white strip or firing any of his guns until the enemy aircraft had moved away. Alternatively there might be a fault in our battery’s receiving set. I have known a case where my observer had forgotten to unwind his 200 ft. length of aerial consisting of a metal cable with a heavy lead weight affixed to the end. The aerial was wound on a hand-operated winch in the rear compartment. Forgetful people landing on any aerodrome trailing a heavy weight were far from welcome, since not only could they kill personnel, but they could damage aircraft on the ground or make holes in hangars.

If having satisfied myself that the aerial had been let out and there was still no reply to my signals, the usual plan (having first wound in the aerial) was to write out a message to the effect that I was getting no answer to my signal and that I suspected a fault on their set, then place the message in a message dropping bag consisting of a weighted fabric pouch to which were sewn a couple of coloured streamers. The

Page 17.

whole of this was rolled into a tight bundle and held in my hand. I then flew low over the battery at about 50 feet and threw the bag down on top of the ground strip. I would then return to our aerodrome and report to the Artillery Intelligence Officer. The latter would report the fault by telephone to the Battery Commander.

Page 18.

Aircraft clocks and watches

On completion of a “shoot” the Squadron Artillery Intelligence Officer always asked me to give back to him the stopwatch he had lent me, before accepting my report.

In the eyes of the Equipment Officer and his staff, the aircraft clock, which was clipped in a holder screwed to the instrument board, was far more important than any other part of the machine. Little did he care if the pilot or the observer were lost so long as his clock was restored to him. Even if you had crash landed on or near the front and had smashed the entire aircraft to smithereens, he would still have expected you to salvage his precious clock!

Page 19.

Encounter with an Albatross

In “How it all started”, I told you how I had “fiddled” my eye test at Cromarty. The sequel to that took place on a slightly misty day in September 1917 over the Ypres Salient, when I thought I saw a French Nieuport Scout approaching me head on and to my intense surprise I saw a stream of tracer bullets passing just under my seat. We almost collided with what transpired to be an Albatross. My observer fired at him instantly with his Lewis gun, which jammed after firing only a short burst. By this time the Albatross had turned in order to press home his attack. I was unable to defend myself with my front Vickers gun, since it was impossible to turn an R.E.8 quick enough even to get an Albatross in my sights; he could turn three times round to my single turn. Hence I decided to drop height in a steep spiral down to about 500 feet. He declined to follow me down among our barrage balloon cables; knowing my way back to Proven aerodrome along the Ypres to Vlamertinghe road, which was lined on both sides with poplar trees, I followed this at about 100 feet, thus escaping our own balloon cables. Having passed these, I climbed to a reasonable height to circle the aerodrome and make an up-wind landing. Having done this, I reported the episode to the Artillery Intelligence Officer. More important still, I took my observer along to the Armourers, where we held an inquest on his Lewis gun. I wanted no repetition of its behavior in case we met another enemy aircraft.

Page 20.

The main utility of British anti-aircraft guns

Oddly enough, I never visited one of our Anti-Aircraft guns and I do not wish to appear too disparaging as to their efficacy. I understand that these were adapted from 6 inch Royal Horse Artillery weapons up ended to fire up into the air. They did not appear to be able to attain anything like the same height as the German Archie, but the English pilots blessed these R.H. guns for their very distinctive yellow sulphur-coloured shell burst, as contrasted with the black colour of the German Archie shell bursts. If I saw yellow bursts, I realised at once there were enemy aircraft about. Our A.A. batteries were excellent in their recognition, and even if they seldom seemed to score a hit, they were first class observers of enemy aircraft.

Page 21

Factory chimney used as observation post against us

It was customary for Intelligence Headquarters to publish and circulate on a wide scale to Army and Flying personnel a general news letter containing items of wide general interest, irreverently tagged by the R.F.C. as “Comic Cuts”.

In one such issue appeared an astounding feat, which took place in the Sector to the south of ours, which I would dearly love to have witnessed. The Intelligence people had learned in some manner - I know not how - that a tall factory chimney near Roulers was being used, with serious results against us, as an observation post from which to direct the fire of German batteries against all kinds of targets in the British area. Some bright person decided that this was a job for the Navy and he proved dead right. It so happened that there had been a ready laid railway line running towards Roulers round a gentle curve. It actually had run across what was then the front line, but of course heavy shelling had pulverised the rails for half a mile each side of the front line. The Royal Engineers repaired the railway track, which was destined to carry a heavy load in the form of a relatively small calibre naval gun of high accuracy. This was mounted on a long low truck, which also carried the necessary mechanism for elevating and lowering the gun. Pointing the gun was effected by moving the gun truck backwards or forwards round the gentle curve. The second truck housed shells for the gun, together with the requisite hoisting gear.

The Battery Commander and naval personnel had offices and living quarters in coaches making up this efficient but somewhat lethal train. The whole outfit, including the rails, were elaborately camouflaged to conceal it from prying eyes, not only enemy aircraft, but also from French, Belgian and British aircraft. It was a very hush-hush affair. Sentries

Page 22

posted to maintain complete secrecy. Belgian peasants and farmers were particularly suspect. It was strange how close they pursued their activities to the fighting area. That part of Belgium had extensive areas covered with hop fields. Proven aerodrome was surrounded by them, as we found to our cost. Due to engine failure, I have on more than one occasion force landed an R.E.8 in a hop field. It ruined the wings and propellers but at the same time furnished an excellent braking effect running into the wooden poles. The Belgian hop farmers did not think it was at all funny.

The time at last came when weather conditions were thought to be suitable by the Navy. Having read every conceivable gauge imaginable, including wind gauge, barograph, atmospheric moisture content and so forth, the great moment had arrived to give the order to fire. The outcome was that the Roulers chimney - a very narrow target - was felled by the very first shot. The Germans up the chimney observing must have come to an untimely end. The Navy must have been pleased at having closed this look-out post once and for all; it had long been a thorn in the flesh to many British batteries in that area.

Page 23

Weak structural details of the R.E.8

No sane person ever looped or spun an R.E.8 because the top wing extensions were very weak and likely to fracture under reverse thrust. In the photo of RE8 2368 the dots over the wings show the bracing wires fitted to take reverse thrust on the upper surface of each top wing extension. This risk was forcibly brought home to me while flying at about six or seven thousand feet over an exploding ammunition dump in the Ypres salient. I sustained two terrific bumps, first upwards and then downwards; the former broke the upper bracing wires on top of one of the upper extensions. When I got back to our aerodrome, I made a very gentle landing and at once had the fractured wires repaired. I felt I had been lucky.

Page 24

High concentration of shells over the lines

During periods of heavy bombardment, the vast number of shells both seen and felt was very noticeable at the various heights at which I used to fly. I use the word “felt” advisedly, because although one did not always see the shell, its close proximity made itself felt by air disturbance, causing the machine to wallow. Gun shells had a flat trajectory, whilst those of a howitzer tended towards a steep curve. Quite a large number of aircraft - both our own and those of the enemy - must have been struck by passing shells and not have known what hit them; they would just disappear without trace. It was always said that we had so many guns and howitzers on the western front that there was insufficient room to park them side by side.

Page 25

The heavy fatigue factor

On referring to my personal log book covering the period from 1st June to 22 December 1917, I recorded a total of 253 hours flying time in No.7 Squadron. The photo of No7 Squadron is at St. Omer. I was then transferred to No.9 Squadron (on promotion to Captain) and for the period from 28th December until 17th March 1918, I recorded upwards of 76 hours flown in this Squadron. The photo of a New Year’s card dated 29.12.17 is for No 9 Squadron.

As an example of the “dawn to dusk” pressure at which my observer and I were working, on 13th August 1917 our first flight was from 5.40 a.m. until 8.40 a.m., and our last flight 5.55 p.m. until 8.15 p.m. These times are typical of the flying hours during the week 13th August to 19th August 1917, when the total flying hours were 29½ hours.

Throughout the time I was in France and Flanders, namely 1st June 1917 to 18th March 1918, I had two periods of leave only, each of one week’s duration. I was by that time exceedingly tired and inefficient; moreover I was suffering from headaches if I went over 8 to 10 thousand feet. In 1918, R.E.8 Squadrons were not supplied with oxygen breathing apparatus.

Page 26

Entry of the United States into the war

Just before I left Flanders, America had entered the war very full of zeal. In our No.9 Squadron was a pilot gifted with the power to mimic. One foggy morning, flying being impossible, we were all sitting in the Mess somewhat bored when our mimic discovered a recent English Newspaper from which he began reading in his best American accent “The United States will be sending over a large number of military pursuit planes capable of 100 m.p.h. etc. etc.” Quick as a flash from a normally taciturn pilot lounging in an armchair came the comment “If that’s all they can do I know who’s going to be pursued!”

Page 27

My return to England

My Commanding Officer in No.9 Squadron, Major Bertie Sutton (later Air Marshall Sutton) decided that I was in need of a long rest. Having consulted our Wing Commander, he arranged for me to be sent home to England for a Medical Board. Accordingly, on 18th March 1918, I left France for good so far as the First World War was concerned. A Crossley tender took me by devious routes to a port of embarkation, because I was now in the hands of Military Movement Control, who operated partly by day and partly by night. It was quite a thrill to be under the care of the Navy and to see “Dover Patrol” at work. Watching a couple of destroyers making circles around our Transport seemingly crawling on its way to our Channel Port always fascinated me.

On reaching England, Movement Control shepherded the entire contents of our Transport vessel into a train bound for Victoria Station. Many of the passengers were serious stretcher cases, whilst others were walking wounded. Each person, of course, carried his or her identity disc around the neck, in addition to a large and very conspicuous label outside.

I was astounded at the perfect organisation of the Movement people; before the train left for Victoria, these large labels already bore the destination of each individual. Having regard to my companions, I felt an utter fraud; my label read “Debility (flying) London General Hospital”. An ambulance met the train at Victoria and whisked me to my destination where I was promptly shoved into bed and had my temperature taken! I was later fed and given the once over by a doctor. Next morning set me wondering whether R.F.C. dawn patrols or hospitals start work sooner; I am inclined to award the prize to the hospitals!

Page 28

Next day I left the Hospital and attended an Air Ministry medical Board in order that this august body could investigate “Debility (flying)”. It took a profound interest in my case and I was given a “complete engine overhaul”, involving all the usual paraphernalia. I expected the finale would be to put me in an enormous glass test tube and heat me with a powerful blowlamp. However, what it did do was to give me a very welcome month’s leave.

Page 29

My posting to Andover

When the month ended I felt fit once more and was quite thrilled on receiving a posting to Andover aerodrome. On arrival there, I was told of the formation of Number 105 and 106 Squadrons R.F.C. to be equipped with R.E.8s and later with Bristol Fighters. They were to be given the thankless job of saving Ireland from Sinn Fein trouble including stopping illegal drilling by the latter.

Page 30

Fin variants used on R.E.8s

When I returned from my stint in France of some nine months, I was somewhat astonished to find that I had to maintain my crusade against the R.E.8 being given a bad name on home Stations. By that time things had progressed to the stage where there were an abundance of R.E.8s fitted with dual control. I was most interested to find that the Royal Aircraft Factory had been experimenting with three different patterns of tail fins. The pattern used in France (and which 105 Squadron used in Ireland) was the smallest of the three. It shows up nicely in the photograph marked A. This fin, whilst prone to let the machine spin, made it lighter to handle. I once tried a machine with the largest fin but it was as heavy as an old cow to handle and, to my mind, quite hopeless. The medium fin I have never sampled, but I know I would not have taken to it. The Factory, I am told, also tried a species of “balanced” rudder cum fin, but I never saw this variant.

Page 31

Training our pilots to fly R.E.8s

Both Squadrons received their machines in April 1918 and began to train their pilots to fly R.E.8s. The pilots were quite raw, very few having had any active service abroad.

We welcomed the arrival.....

of a United States contingent at Andover comprising one officer, several N.C.Os and a gang of highly enthusiastic and competent mechanics. Supervised by one of our own (British) mechanics, I gave our U.S. friends the task of de-coking an 140 h.p. R.A.F. engine. In those days there were no such things as “Air Publications”. Our mechanics had to work from first principles without Instruction Books. With their fortunate excess of manpower, they fell upon this engine and, in no time, had it stripped, de-coked, valves ground in - one man to each cylinder! - and re-assembled. Moreover, it ran superbly after its lightning overhaul. One day there turned up at Andover our Inspecting Wing-Commander flying his much coveted Sopwith Pup, which he always had kept in immaculate condition. He was an ex-cavalry officer who likewise kept himself very smart. I told our U.S. friends to fill his Sopwith with “gas” and generally to service and clean the machine. Having completed his inspection of our officers and machines, he returned to the tarmac and was about to climb onto his Sopwith, after being saluted punctiliously by the British personnel (of course, there being no multi-star general present, not a single salute was given by our U.S. allies), when he looked at one of the Sopwith’s R.A.F. wires and saw a tiny spot of dirt and told an American mechanic to remove it. A “Bateman picture” ensued when that mechanic replied in a nasal accent “I guess you’re a mighty particular sort of guy”. We were relieved when his Sopwith Pup started and he took off without further trouble!

Page 32

Beware of photographers

I was nearly slain by an enthusiastic R.F.C. photographer, whom I took up one day while at Andover aerodrome. He was, of course, operating from the rear (observer) cockpit and, somewhat incautiously, I did not check the stowage of his impedimenta; this including in addition to a hand-held camera, a stack of wooden boxes holding his plates. The rear cockpits of R.E.8s were never floored adequately enough to prevent objects placed thereon from falling through and getting lost or jamming the controls. On the completion of our photographic mission, I tried to land on the aerodrome coming in fairly fast and made to flatten out for a “three point landing”, only to find that the control stick was locked in the backwards direction. I quickly slammed the throttle fully open and only just avoided hitting the deck hard. I then climbed up to height at which I could safely turn around to see what had locked the stick. The answer - don’t allow photographers with no structural knowledge of aircraft to pile their luggage so as to impede working near the fixed stool! I believe that particular photographer did not repeat this performance, since he scared us both stiff.

Page 33

Take off for Prestwick and the peril of a Solway mist

I took off from Andover on 14th May 1918, with my flight of five young pilots for Ayr, flying first to Hooton Park, Liverpool, to re-fuel. Here we arrived safe and sound. Having filled up, we continued the journey to Ayr, with the intention of crossing the Solway Firth. I could get no weather report at Hooton park before taking off and reckoned without the deadly Solway mists which got lower and lower, forcing me down to about fifty feet over the sea. It was clear to the west, but it was very obvious that I had insufficient petrol to take the westwardly course round the Mull of Galloway to Ayr and Prestwick, where there was a good aerodrome. I had to make a quick decision to go north, leaving Wigston to port and follow the single track railway line to Newton Stewart. I glanced back and saw my flock of five following me as we entered the railway cutting in line astern. To my horror the cutting began to rise and the mist to lower as we approached Newton Stewart, but we had passed the point of no return and it was impossible to turn round in a single line cutting. Suddenly a bridge and signal loomed in sight forcing me to pull upwardly into the mist to clear the bridge and signal. I came quickly downwards back into the cutting after passing the bridge. I had to repeat this performance as more bridges and signals came into sight; then I realised the land was starting to fall and the mist tending to clear. My passenger was an excellent mechanic but no navigator. I never did know when I got to Newton Stewart, but suddenly the cutting opened out and I saw the sea ahead. Only then did I dare consult my map and turn right towards Ayr. Looking astern, I could see only one of my flock following me like a leech. Later I learnt that the other four machines tried to turn off and land. They crash landed, but amazingly no-one was hurt.

Page 34

At last we reached Ayr and landed in the mist on a field sloping down over the edge of the cliff. We climbed out and, finding we were very short of petrol, decided to go no further until we got more from somewhere. Presently we saw some figures coming towards us and on getting closer they turned out to be in R.F.C. uniform. We asked for petrol which they offered to bring. One of these persons was a pilot wearing decorations, who expressed great surprise that we had been flying at all in these weather conditions. I asked his name and he replied “McCudden”. Apparently he was instructing fighter pilots at Prestwick nearby. After re-fuelling, I insisted on going on to Prestwick with the only other remaining member of my flight. My own machine was grossly overloaded with odds and ends which I had hastily collected from our Andover mess knowing them to have been left behind by their owners inadvertently.

Take-off from Ayr, if made into the wind, meant doing so uphill and I knew my machine would never do it. Consequently I took off down-hill with the wind behind me going very fast over the cliff and I was only fully airborne just in time to clear the sea - a very close thing. I made for Prestwick, which even in those days was a very much flatter and longer aerodrome on which to land. On arrival, I learnt the fate of my four other pilots and passengers; then I telephoned Andover aerodrome and reported the score, namely, two safe arrivals at Prestwick and four damaged. We stayed at a lavish hotel in Prestwick for a few days awaiting the arrival of the four other pilots and passengers, together with four replacement R.E.8s which, incidentally, arrived from Coventry very quickly. With some apprehension, C Flight once more consisting of six machines, made the sea crossing on 17th May 1918 to Aldergrove aerodrome, which was at that time little more than a series of rough grass fields

Page 35

with the hedges and banks bulldozed flat. To my intense relief, all six machines landed intact and without damage to their undercarriages. Quite a good effort considering no wind-sock had been erected, there was no visible smoke and each pilot interpreted the wind direction according to his own idea. No two were the same and yet, mercifully, none hit the other! Some form of aerodrome control would have been appreciated.

Page 36

Location of the two Irish Squadrons

Nos. 105 and 106

105 Squadron was located initially at Strathroy aerodrome, Omagh, Co. Tyrone, and from there it patrolled the northern half of Ireland, whilst 106 Squadron took care of the southern half of Ireland, being based at Fermoy, Co. Cork. From that time I lost all contact with them.

Page 37

105 Squadron moves to Omagh

On the following day, C. Flight flew on to Strathroy aerodrome at Omagh, A and B Flights having already arrived; likewise our C.O. Major Joy, a pleasant Canadian. Our Squadron was now complete and the various flights began their patrols in earnest, after being issued with the appropriate maps. The Squadron had its own photographic section.

Each flight had its own Bessoneaux type of Canvas Hangar. At that date there were no public telephones in the smaller Irish towns; for example, towns like Athlone, Galway, Mullingar, Clifden, Roscommon or Castlebar were all devoid of the telephone. But towns and villages with post offices had a telegraph system and one could send a telegram, the contents of which were open to the world!

The Royal Irish Constabulary (R.I.C.) barracks had a private telephone system of their own; they were helpful in allowing its use by the army, naval and air services for official business.

If secrecy was important, it was advisable to encode the message.

Our Squadron Signal Section rigged up a Station Communication system, using field telephone sets.

In carrying out our patrols, the three flights changed their “beats” each week, thereby giving their pilots and observers a wide knowledge of the Squadron territory. We kept Headquarters Flight informed of the direction of the proposed patrol before take-off; this was to assist in finding the missing machine in the event of forced landings, which were all too numerous.

The local landowners were friendly to us and kept on inviting us to numerous cocktail parties and also to dances at their homes; we did our best to repay them, and whilst we had no

Page 38

parties out on the aerodrome. An aeroplane was a complete novelty to most of the locals and we gave a number of flying displays, while we were at Omagh. On one occasion we allowed the people of the town on to the aerodrome to see the aeroplanes and by way of a joke we hung heavy chains and hooks on two of the R.E.8 undercarriages; the mechanics, when asked by the people what they were for, replied that these were used for hooking up anybody thought to be engaged in illegal drilling!

Little did we ourselves then appreciate that we were the inventors of the technique of “snatch pick-up” used by the glider towing aircraft in the Second World War.

Our Squadron got a number of requests from places like Londonderry, Dundalk and Portadown to land an aeroplane and help parties given in aid of recruiting campaigns or other meritorious wartime causes. Our C.O. encouraged these “landings” and I personally took part in quite a few. We caused much excitement and sustained some thrills ourselves when taking-off afterwards. We had to train locals on the spot to hold the machine while we ran the engine to maximum revs. and then to let go on a pre-arranged signal.

Page 39

Picnic on Bundoran Beach

On a very warm afternoon in June 1918, three of us decided to combine business with pleasure. Taking a picnic tea and gramophone, Lt. Harrison, Lt. Dick, myself and three other officers donned bathing dresses under our scant flying clothes, set forth in three R.E.8s to Bundoran Beach arriving at about half tide. By prior arrangement with my other companions, I was to test the hardness of the sand by making one or two dummy landings. Having satisfied myself that the beach was safe, I made a final landing, stopped my engine and got out on to the sand, which was nice and firm. I then signalled to the other two machines to land, which they did. There did not seem to be a living soul about. We unpacked the gramophone and picnic baskets. We sat on the sand (which was lovely and dry) shoved on a gramophone record and started to have tea. After about twenty minutes, a bathe was suggested, so we packed up the baskets and gramophone. We were on the point of removing our flying clothing to enter the sea, when Harrison drew my attention to the fact that the empty beach was so no longer. On the contrary about a hundred people had congregated just above us on the sand dunes. A man, who appeared to be their leader, perched himself on an old wooden box and started to incite the crowd to hostile action. The leader told the crowd - pointing to us with his hand - “These fellows have been sent by the wicked English to kill you all”. Rather stupidly, we had brought no firearms with us. We had even left our Lewis guns at Castlebar. The only effective weapons were the Vickers guns on the three machines. But only effective AFTER the engines had been started. I told Harrison that I would swing his propeller for him. The engine responded instantly, but in so doing gave a prodigious backfire, with black smoke belching from its two vertical

Page 40

exhaust pipes (see Photo A). The leader fell off his box and ran away like hell, closely followed by the rest of the crowd. All of us returned safely to Castlebar without more ado. God bless engines that backfire!

Page 41

Division of 105 Squadron

In August 1918, 105 Squadron was divided into two parts in the following way. Our Commanding Officer, Major Joy, with A and B flights, together with Headquarters flight, moved to an aerodrome at Oranmore, Co. Galway, whilst I was ordered to take C flight with six R.E.8s, our share of personnel and transport to Castlebar, Co. Mayo. Prior to this move, Major Joy flew me in his own R.E.8 No. E29 to explore the field at Castlebar and see whether it would be possible to make it into an aerodrome. When we landed we both got a bit of a shock, as not only was the grass very long but there were too many cows about. Before touching down, I tried to scare them away by firing a Very pistol, but the cows thought this was done to amuse them! We walked round the field, which according to our map was about 90 acres; we also took a look at the nearest public road running between two granite walls, built loose, i.e. without mortar, these walls enclosing the field.

When we were ready to fly back to Omagh, whence we had come, I chased the cows clear with a stick and got down to the prop swinging procedure. Incidentally, R.E.8s had a hand-operated starting magneto operated by the pilot in his compartment. I called out to Major Joy “Switches off, suck in”. To which he replied “Switches off, suck in”.

I thereupon put my shoulder against one blade of the prop with my arms holding that blade tightly and started to rotate the four-bladed propeller against the high compression of the 140 h.p. R.A.F. engine. The next thing I knew, I was flung to the ground alongside the wing tip and the engine was running! He had failed to switch off; this was a piece of gross carelessness on his part. I think he was very shaken by the episode, but I was glad he did not stop the engine to say “Sorry”, since I was not anxious to have to repeat the

Page 42

up procedure. We got back safely to Omagh and neither of us alluded to the incident, nor did I tell my comrades in the mess about it. Quite apart from this, I did not like being flown by other pilots.

Page 43

Move of A and B flights to Oranmore and of C flight to Castlebar

In August 1918, we received orders from our General Officer Commanding the Royal Flying Corps in Dublin to vacate Strathroy aerodrome at Omagh. A and B flights, together with Headquarters flights were to go to Oranmore aerodrome, near Galway, with Major Joy. I was sent with C flight and its six R.E.8s and personnel to Castlebar, Co. Mayo.

After taking local advice, we sited our Besonneaux hangar parallel to and about twenty yards away from the public road, in the shelter of a wood of fir trees, with its back to the prevailing wind. Contractors were employed to lay down an “apron” in front of the hangar, the apron taking the form of rough granite stones quarried locally and levelled off with granite chippings. We were not allowed the luxury of a tarmac coating on the apron, although the 90 acre field in which the hangar lay was wet and soft. The outcome of this was that we had to make reiterated pleas to the contractor to keep on extending the apron and eventually lay a runway - something of a euphemism - as the machines sank into the ever increasing mire. A ridge some ten to fifteen feet high ran across the whole field, but fortunately it was a gentle ridge making it possible, if the wind so required, to taxi over the ridge with mechanics holding the wing tips.

Page 44

The fury of an Irish gale

We had hardly been there ten days when we learnt what an Irish gale was like; we reckoned it was 100 m.p.h. plus. We spent most of one day and part of the night with all hands filling sandbags with soil dug up by the contractors when they were laying the apron. These were used to pile on the hangar (wooden) feet and all along the lateral canvas. We nearly lost our hangar that night, to say nothing of the machines inside, which were lashed down with screw pickets and ropes at each wing tip, as well as over the fuselage near the tail. The gale blew down many of the fir trees. This was the only blessing accruing from it, since we had permission from the adjoining land owner (given before the gale) to cut fallen trees for fuel. We were not slow to take advantage of this kindness.

Main water was piped on to our camp, but although the town of Castlebar ran to a gas works and electricity supply, neither had been laid on to our camp, being too far out of the town.

We had to rely on paraffin lamps for light and heat. We were lucky in having a workshop lorry standing at the corner of the hangar, the engine of which generated 110 volts D.C. I gave permission for this to be used until 10 p.m. each night to light the camp.

Page 45

Shooting of Resident Magistrate

Having got settled down, we started patrolling the surrounding country with our R.E.8s. One day we had a report from the R.I.C. that the Resident Magistrate had been shot at Westport, which lies on the west coast of Co. Mayo, by the sea.

The Officer Commanding the Border Regiment (incidentally he was what was then termed “The Competent Military Authority” for short C.M.A.) asked me to come and see him which I did. He requested me, as soon as possible, to fly over Westport and “show the flag”. I led, on the day after the Resident Magistrate was shot, a flight of five R.E.8s over Westport, where we fired off a lot of ammunition from our Vickers guns. The Vickers guns were carried on the port wing. We also fired off more shots with our Lewis guns mounted on the rotatable Scarf ring of the observer’s compartment.

Each R.E.8 had a pair of bomb racks, located close to the port and starboard wing roots and carried two pairs of 20 lb. bombs, which we also dropped into the sea. We did our best to ensure that no member of the public was hurt. At least, we “showed the flag” and made a lot of noise!

The C.M.A. told me that the Irish Authorities were very worried that they might not have enough manpower in the west of Ireland to cope with the activities of Sinn Fein if a serious confrontation arose. British Intelligence was aware that German submarines were using bays on the west coast in which to land for the purposes of getting fuel, fresh water and food supplies, which the Sinn Feiners were all too ready to give them and thus embarrass the U.K.

Page 46

Naval motor launches

Our Navy kept a few small M.Ls in the various west coast bays. I spotted an M.L. lying at anchor just off Westport when I was carrying out a solo patrol there in my own R.E.8 2368; I observed that this M.L. was displaying on her deck the wrong code sign for the day. Was it friend or foe?

I drew my observer’s attention to this fact and we decided to draw the skipper’s notice to his error by the only means of communication available to us. We had no radio so I wrote a message “Correct your code sign for the day” and placed this in a message bag. I then flew low over the boat, just clearing the mast, and more by luck than good judgement managed to land the message bag on his deck. My manoeuvre brought almost the entire crew on deck. I climbed to three or four hundred feet circling around to await results. The code sign was promptly rectified. I then flew low alongside and waggled my wings, receiving friendly waves from all on deck. More obvious British tars one could not imagine. I was glad I had not taken hostile action and loosed off my bombs. I had probably caught them at lunch time and it would have disturbed their pleasant afternoon snooze on a nice calm and very hot day.

Page 47

Arrival of Bristol Fighters

A few weeks later, three Bristol Fighters were delivered to Castlebar aerodrome and three R.E.8s taken in exchange. We were fortunate in having amongst our number a Lt. Harrison (now deceased) who had flown a Bristol in France late in 1916.

He showed me all “the taps” and gave me some tuition, he sitting in the pilot’s seat, whilst I sat in the observer’s seat. Having got the hang of things, we then reversed seats. Other than the “unspeakable” large Armstrong Whitworth with its Beardmore engine, the Bristol was my first experience with a water cooled engine.

Harrison was kept busy teaching the other pilots in our flight. We were given no literature on the Bristol, not even a spare parts list. Our engine mechanics had no training to service a Rolls Royce 260 h.p. Falcon. We sadly lacked the advantage of having at least two sent to Derby on an engine course. On this subject more anon.

Page 48

Alcock and Brown cross Atlantic

On 15th June 1919, we received instructions by telegram from the Air Ministry that Alcock and Brown were trying to cross the Atlantic from west to east in their Vickers Vimy aircraft and, to the best of our ability, we were to maintain a watch for them. The day was exceedingly misty and raining - what the Irish call “a soft day” - and I took off from Castlebar in B.F. 4351 going along the road to Clifden, which I knew well, since I had both gone over it by road and flown over it on fine days. I was going with caution to avoid the cluster of aerial masts forming part of the equipment of the Clifden Transatlantic Wireless Station, the tops of the masts being lost in the mist (they were not illuminated in those days) and hence were a hazard to aircraft.

Quite suddenly I saw the Vickers Vimy standing on its nose in the bog: the pilots had been lucky not to hit any of the masts. Much as I longed to land by the Vickers Vimy, I saw no point in hazarding my machine and joining the pilots in their plight in the bog. Hence I made my way back to Castlebar as quickly as the weather conditions permitted. Luckily, conditions improved near Castlebar. I telegraphed the Air Ministry to report my find. I then took a Crossley tender and drove as fast as the road would allow back to the Clifden Radio Station. By the time I got there, Alcock and Brown had hired a car in Clifden village and were taken to Galway.

After contacting the boss man of the Radio Station, I put on Wellingtons and wallowed out to examine the Vickers Vimy with its two 350 h.p. Rolls Royce Eagle Mark VIII engines. I later learnt that they had less than 50 gallons of petrol left, I thought they were very brave men. Having brought my own hand camera, I took a series of photographs for my album. I then arranged in Clifden for a military guard to be mounted

Page 49

until the Vickers Vimy could be collected. Then I drove back to Castlebar.

Some three or four months later the Sinn Feiners completely destroyed the whole station, masts and all. To this day it has never been rebuilt.

Between 1950 and 1960, the Irish Government erected on the top of a hill about a mile from the actual landing point an attractive granite memorial consisting of a bit of wing and tail of an aircraft. On the base of the memorial is a plaque giving the names of the two pilots, the date of their landing and particulars of the machine and its two engines; the road has been widened and flattened adjacent to the memorial to provide parking space for a few cars. The plaque invites attention to a rock painted white and located in the bog at the precise landing spot. Many tourists drive up to the memorial and the more energetic walk along the bog road which is as rough today as in 1919.

Clifden has blossomed into a prosperous town; an hotel called the “Alcock and Brown” caters for tourists, chiefly Americans. Postcards are sold in the town showing the Vickers Vimy as it landed.

Page 50

I lead the flight into trouble to their mutual advantage

We were a wild and unruly lot and had little respect for the sporting rights of local estate owners, as this tale will illustrate. Feeling bored one Sunday afternoon after a good lunch, “Satan found some mischief still for idle pilots” to do.

It occurred to the Flight that a little post-prandial aviation would meet the occasion, so we commanded our six R.E.8s to be brought to the door of the hangar.

We then proceeded to raid the Flight armory, each grabbing the weapon of his choice, ranging from 12 bore shot guns, Lewis guns and revolvers. Our R.E.8s were gunned up with Vickers guns firing through the prop. Having invited our selected mechanics to join in the Sunday afternoon fun, the cortege took off.

In the close vicinity of the aerodrome, we found a network of duck ponds, which we proceeded to shoot up from a very “naughty” altitude; even then I doubt if we hit anything.

Little did we know that we had trodden heavily on the corns of a certain Major Dominic Brown (now deceased) until the following Monday, when a polite letter was delivered to our Guard-Room tent asking us kindly to refrain from poaching on his game reserves. I decided to present an immediate apology in person, which resulted in very cordial relations being established with Major Brown and his household.

Page 51

Our mixture of aircraft at Castlebar

While at Castlebar I had the opportunity to compare the R.E.8 with the Bristol Fighter. Our mixed bag comprised Bristol Fighters with the 260 h.p. Rolls Royce “Falcon” engine and the older R.E.8s with the 140 h.p. air cooled “RAF” engines. In those now dim and distant days the letters R.A.F. did not yet stand for Royal Air Force which had yet to come into being. They signified Royal Aircraft Factory, an establishment that was the butt of many articles by C.G. Grey of “The Aeroplane”.

As flight commander I could choose my own aircraft. My logbook shows that I usually flew R.E.8 No 2368 while my preferred Bristol Fighter was F 4351. Depending on our crash and serviceability rate our strength in C Flight varied from seven to eight machines. In the photo (photo A) of RE8 2368, behind the tail fin of the R.E.8 can be seen a rare instance of a Bristol Fighter with a four bladed propeller. The photos (photo B and photo C) of F4351 show two Bristols with the more usual two bladed propeller.

I do not know when the so-called “Hucks” starter came into use but we always had to start up our Bristols with a string of at least two mechanics holding hands and swinging the propeller. This presented no difficulty even on a cold morning. There is an example of both an R.E.8 and a Bristol Fighter at Duxford, and an airworthy Bristol Fighter at Old Walden in the Shuttleworth Collection.

I could only wish that we had had Bristol Fighters when I was flying over the Ypres Salient. They were so much more flexible than the poor old R.E.8. For counter battery spotting 70 m.p.h. was too fast and the 140 RAF engine had to be nursed by throttling back to about 60 m.p.h. However when returning to base in a hurry 70 m.p.h.was desirable, and

Page 52

when nursing the R.E.8 I reckoned to have an engine failure every 60 hours of flying. With the Bristol you could throttle back to 55 m.p.h. on the level but you had a far greater turn of speed for combat - or escape!

Page 53

Fostering good relations with the Sinn Fein fraternity

Wherever possible, I always tried to foster good relations with the Sinn Fein fraternity; in this episode it worked well. At Castlebar aerodrome, an Irish farmer, with an accent as broad as his body, rolled up one day asking for help. I happened to be standing on the tarmac in front of our hangar with my Flight Sergeant. I asked what was troubling him and he replied that on his farm he had a large paraffin oil engine for operating turnip cutters and the like; a piston of the engine had allegedly seized. Politely I explained that this was a job for one of the local garages of which there were several quite bright ones in Castlebar. I named two or three, but he said bitterly one of them had tried and failed.

We took his name and address and I promised to let him know; I then thought I would find out more about him from my friends at the R.I.C. barracks, who told me that he was a rabid Sinn Feiner and must be in dire trouble to have come near us at all.

My Flight Sergeant and an engine mechanic drove to his farm that evening with a hefty tool kit. After about half an hour they managed to free the seized piston. He had apparently used a 56 lb. weight with which to try and hammer the piston home; the latter resented such treatment!

That farmer showed his gratitude by having not only the Flight Sergeant and mechanic, but other members of the Flight, to regular Sunday afternoon teas at which they were given eggs and other farm “goodies”.

Page 54

I indulge in breaking a strike and King’s regulations

The other side of the picture shows how a young and would-be helpful fellow like myself can get into trouble. Every day one of our lorries called at Castlebar railway goods yard for stores. One of the town bakers asked our driver, a stalwart Scot, Jock Hunter by name, to bring a couple of sacks of flour down to his bakery. The good natured “Jock” obliged and thought no more of it.

The next day I got a letter from the Bakers’ Union to the effect that I had been “strike breaking”. To make me quake in my shoes, that letter was delivered to me by hand by an R.I.C. Sergeant. I intimated in no uncertain terms that I was wholly unaware that there was a strike and, in any case, my men must draw their bread rations.

I consulted King’s Regulations, which pointed out that to use troops to break a strike constituted a serious offence. I was only mildly repentant, telling Jock “off the record” not to do it again. The outcome was that our men and officers got our bread rations; I ignored the Union’s letter, the strike ended abruptly, I earned the gratitude of the Castlebar Barracks by saving them the task of violating King’s Regulations. I had transgressed, but as it was not my intention to stay in the Crown Forces after the war, I could not have cared less. I heard nothing more of the episode.

Page 55

The exploits of Lt. Dick

One of our Castlebar pilots, Lt. Dick by name, was a Glaswegian with the broadest Scottish accent. He was a very wild but likeable lad having a passion for low flying, it being his chief joy to try and roll the wheels of his aircraft on the hangar roof. A rare and strange training machine, namely a D.H. 36 had just been sent to us. It had a very marked camber on the leading edge of its four wings, from which it got the nickname of the “clutching hand”. This machine (powered by a 90 h.p. air-cooled R.A.F. engine) could barely fly at more than 50 to 60 m.p.h. flat out and stalled as low as 30 to 40 m.p.h.

Dick thought the D.H. 36 was the “cat’s whiskers” for his hangar roof antics, but not content with that he proceeded to beat up the Castlebar lunatic asylum (he chose an appropriate place to do it!) by hitting and flattening a beautiful springy hedge in Doctor Ellison’s garden, who was the Medical Officer for, inter alia, the asylum. I had to go along, with a breakdown squad to the asylum and make my apologies for Dick’s conduct. As things turned out Dr. Ellison thought it was funny and our officers (including Dick) became his firm friends.

Page 56

Lt. Dick and I nearly break a Bristol and my skull

Some days later Dick started to take off on a patrol from our aerodrome in a Bristol. Wanting to give him some instructions about this patrol and before he started to move, I hopped up on the port step holding on, with my right hand, to the observer’s compartment. The observer had his head down inside fitting his helmet and goggles, so he did not see me. At that very moment Dick slammed his throttle open, with the result that the slip stream caused me to lose my grip partially as the machine began to accelerate. My first thought was not to try and jump clear for fear that the tail plane would damage my back as it hit me, so I rolled myself into a ball and slithered backwards down the fuselage, where I got entangled in the tail plane bracing wires. I managed eventually to wriggle free, by which time poor Dick was pushing his stick forward and wondering why his tail would not lift. By this time he was nearing the end of the runway and had to clear two loose Irish boulder walls and a public road.

I reckon that when I rolled off his tail on to the soft grass, the machine was doing every bit of 45 to 50 m.p.h. I thought I would never stop rolling and, when I did, I saw countless stars. The “milky way” was put in the shade. Dick told me later that the tail of his machine shot up quickly as I came off it, requiring a speedy corrective action on his part.

Page 57

No Doctor at Castlebar aerodrome

If a crash took place at Castlebar aerodrome, or if any of our personnel was ill, we had no resident medical practitioner available. Either we had to call Dr. Ellison, an excellent doctor, or we were faced with Dr. O’Flaherty who was rarely sober. Castlebar did not possess any other choice. Lt. Harrison was suffering from a severe attack of influenza, at a time when Dr. Ellison was on vacation. We were driven to seek the tender mercies of Dr. O’Flaherty. On his arrival, I conducted him to Harrison’s tent, where our sick pilot was given (in addition to a bottle of Aspirin tablets) the following advice “Go easy now on the whiskey, don’t take more than six glasses before noon!”

On this somewhat unorthodox, albeit expensive, prescription, Harrison’s recovery was speeded up and the morale of the patient rose.

Page 58

Lt. Dick and “Pitot” his dog

Dick owned a most lovable mongrel rejoicing in the name of “Pitot”. This name was coined from what I believe to be a now extinct instrument usually mounted on the forward port wing tip strut of earlier aircraft. Its purpose was to operate the Air Speed Indicator (A.S.I.).

Dog Pitot was often taken up flying by Dick, sitting on his lap. He had the disconcerting habit of barking and jumping at props while machines were being run up outside the hangar. One day we thought the inevitable had happened, when Pitot was struck by the blade prop of an R.E.8, whose engine began to vibrate so violently that it had to be stopped at once. Pitot’s tough cranium had broken off a 3 foot mahogany strip from one of the blades. Pitot ran away yelping, but five minutes later he was again trying conclusions with propellers. We never cured him of this habit.

Page 59

My periodical medical boards