What is England? - Transcribed from Simon Schama's Shakespeare:

What is England? In Shakespeare's day the answer wasn't at all obvious. The Reformation had left the country isolated from Catholic Europe. Alone in the world now, the English wanted to know who they were. What made them unique? Shakespeare's eccentric but inspired response was: Sir John Falstaff. The magnificent star of Henry The Fourth Parts 1 and 2. The fat knight who has enchanted audiences since he first took to the stage in 1597.

Many have explored the mystery of Falstaff's universal appeal. He's a liar, a cheat and a glutton, and yet we can't help giving him our hearts. For me it's that in him we find distilled so many of the hallmarks of Englishness. Wit, candour, generosity, irreverence.

Falstaff has to be big because almost all of England and its pulsing, meaty, rowdy and uncontainable life flows directly through him. He's the living embodiment of a small country which suddenly has an outsize sense of itself.

Like any true Brit, Falstaff displays a healthy scepticism toward authority. In one of his greatest speeches he deflates the pretensions of the English upper class. Surrounded by dead bodies on the battlefield, he asks:"What is honour? A word. What is in that word 'Honour'? What IS that "Honourrrrr"?Airrrrrrr! A trim reckoning.Who hath it?He that died a’ Wednesday. Doth he feel it? No. Doth he hear it? No. Is it insensible then? Yeah - to the dead".

Rather than wasting time venerating power and ceremony, Falstaff devotes himself to life's simpler pleasures: friends, fun, eating, drinking. He sees life as a meaty, heady thing, to be consumed to the dregs.

Falstaff's audacity and many vices made him an instant hit. Whenever he appeared the playhouses were full. Understandable really. The Elizabethans needed something to smile about. In the mid-fifteen-nineties London was gripped by riots, sparked off by sky-rocketing food prices. Falstaff 's super-size belly offered hungry audiences a temporary escape from hard times.

It's not just Falstaff's girth that's bursting at the seams, it's also his language which is abundant and baggy and brim-full to overflowing with intoxicating exhilarating verbal juice. You can almost taste the flavour and the savour of England in it:"There's no more faith in thee than a stewed prune""His wit is as thick as Tewksbury mustard""Hang me up by the heels for a rabbit sucker"

Falstaff enchants us all with the promise of a life of absolute freedomAnd it's this that wins him the friendship of Prince Hal, the heir to the throne, and Falstaff's drinking companion.For Hal, Falstaff represents the good life: cakes, ale and laughter - the complete opposite of his father, King Henry the fourth.

Unlike Falstaff who lives in a carnival Merrie England (constant booze-ups, joke-slamming with the prince), Henry The Fourth is trapped like all of his courtiers in a Death Star, where everyone moans and plots from inside the steel casing of their dark armour.

Through Falstaff, Hal indulges in a fantasy of a life without responsibility But the problem is just that. It's a fantasy. Falstaff's world is a childish Never Never land that all adults are destined to leave.

When his father dies, Hal can no longer ignore the reality of his position. He's about to be crowned King of England. In order to rule he must banish Falstaff, The Lord of Misrule. "I know thee not old man. Fall to thy prayers."

What we witness is not just a repudiation of Falstaff, the friend, the fellow-reveller, but a demolition. A living death. And of a peculiarly English kind. The social cut. As sharp and as lethal as a blade.

"My sweet boy! My heart" cries Falstaff, reaching out.

The rejection of Falstaff is one of the most tragic scenes in all of Shakespeare. Because despite the heavy strain of sinning, Falstaff's England is a place where laughter beats fear. Truth beats grandeur. Cults of honour are exposed as preening lies. He represents a commitment to honesty and freedom which the English still hold dear. Banish Jack Falstaff - and banish all the world.

Sent from my iPad

Phil’s History:

A ‘work in progress’ family history website starting from an Archer family of South Oxford, who were freemen, brewers, haulage contractors, and first ‘Archer & Co’ then ‘Archer Cowley & Co’ furniture removers in the 19th and 20th Centuries, inter alia, to whom are linked by marriage the Penfolds and Wells of Southwark and Surrey, the Reeds of Devon, the Gilders of Oxford and Hinckley, the Morgans of Petworth, Sussex, the Garners of Middleton, Lancs and many others. There are connections via Phil and the present generation (born 1930s/40s) with a patent law firm known as "UD&L" with motor-racing and Scottish antecedents.

Site Navigation[Skip]

- Home

- Introduction

- Contact Form

- On Brexit

- Archer Cowley & Co:

- Recently-added pages and text and graphics:

- Map/index/menu

- Book-type index page:

- General Family Tree

- Links

- Who are these people?

- Pre-WW1 Aviation

- Anne Archer Archer’s bedspread:

- Somerville House:

- Present Generation:

- Tree link to Phil’s generation:

- Phil’s own generation (just pre-WW2/during/1940s):

- Family photo album (and related graphics):

- Phil’s Cousins (his father’s brother, Arthur Archer’s family):

- Phil’s clubs and other interests:

- Contact Form

- WUD’s Reminiscences:

- Names mentioned in "Persons of Skill & Probity":

- Technical people Phil has worked with:

- Jacques Loriot and Cabinet Fedit-Loriot of Avenue Hoche, Paris:

- Phil’s Blog:

- Michael's cv (as a Freeman of Oxford):

- Steam

- Timeline

- Gwenda Morgan:

- The New Zealand Family

Sidebar[Skip]

Gray’s Elegy:

For who to dull forgetfulness a prey,

This pleasing anxious being e'er resigned,

Left the warm precincts of the cheerful day,

Nor cast one longing lingering look behind.

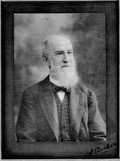

Phil’s maternal great-grandfather.

William Wells, Chrysanthemum-culturist, exhibitor, and writer, of Merstham, Surrey.

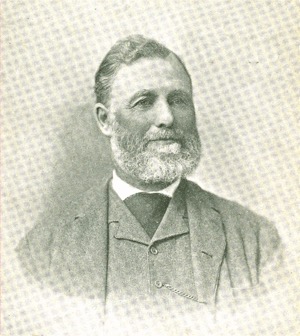

Phil’s paternal great-great uncle, James Archer (1836-1922): founder of Archer Cowley & Co. (click on the image for full-size view).

PBA with Michael and Edward and Gwen on 7.7.2009:

Caption:

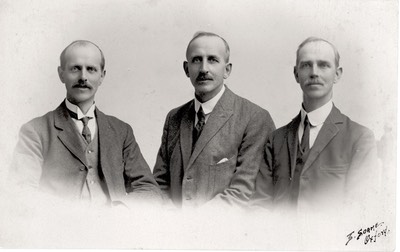

So, this is the nearest photo for comparison with the above one of WGRA and Ernie and Bert, that I can find. Three grandson’s of WGRA and their centenariian mother, on her 100th birthday.(20.3.17). A lawyer, a sportsman, and a theologian, (to contrast with a Transport Contractor, an Automotive Industry importer/exporter, and a Thames Consevancy Officer); born in the late 1930s, early 1940s, and late 1940s respectively, about two generations after WGRA and his brothers of course. Living in Rutland, London, and Oxford, respectively - to contrast with William, Ernest and Herbert, who lived in Oxford, Netherlands, and The Thames Valley (Tilehurst), respectively.

(Click-on the above thumbnail for full-size image of) Post-war steam heyday: Stanier Black 5 at Oxford MPD, just over the canal from Jericho, in the 1950s. Both locos seen here in one of Phil’s teenage-years photo-collection show unmistakably the Swindon influence of Churchward’s taper boiler and Belpair firebox. (pba.Ensign Selfix.16.on.120:Ilford FP3 developed in ID11).

Below (click on the thumbnail) High Street, Oxford, early on the morning of 1st January, 2000. Captured by my brother Edward. No traffic. No buses. No people. Unbelievable. It’s as it must have been almost 100 years before when WGR Archer photographed St Aldates. Click here to compare.

...Dreaming of days gone by...

The Kerry Dances:

Oh, the days of the Kerry dancing

Oh, the ring of the piper's tune

Oh, for one of those hours of gladness

Gone, alas, like our youth, too soon!

When the boys began to gather

In the glen of a summer's night

And the Kerry piper's tuning

Made us long with wild delight!

Oh, to think of it

Oh, to dream of it

Fills my heart with tears!

Was there ever a sweeter Colleen

In the dance than Eily More

Or a prouder lad than Thady

As he boldly took the floor.

Lads and lasses to your places

Up the middle and down again

Ah, the merry hearted laughter

Ringing through the happy glen!

Oh, to think of it

Oh, to dream of it

Fills my heart with tears!

Time goes on, and the happy years are dead

And one by one the merry hearts are fled

Silent now is the wild and lonely glen

Where the bright glad laugh will echo ne'er again

Only dreaming of days gone by in my heart I hear.

Loving voices of old companions

Stealing out of the past once more

And the sound of the dear old music

Soft and sweet as in days of yore.

When the boys began to gather

In the glen of a summer's night

And the Kerry piper's tuning

Made us long with wild delight!

Oh, to think of it

Oh, to dream of it

Fills my heart with tears!

(Added 11.7.18):

There is so much good in the worst of us, and so much bad in the best of us, that it ill-behoves any of us to find fault with the rest of us. (James Truslow Adams).